Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

Innu Nation Grand Chief Etienne Rich says he was “grateful” for a heads-up on the meeting of Newfoundland and Labrador premier Andrew Furey and Quebec premier François Legault last week in St. John’s. There was a follow-up call from Furey and meeting on Monday, also in St. John’s. Despite the level of engagement, he told Atlantic Business Magazine, none of it means the Innu Nation has given its blessing for province-to-province talks about Churchill Falls and further hydroelectric development on the Churchill River.

Innu Nation Deputy Grand Chief Mary Ann Nui and other senior Innu Nation officials joined Rich for the meeting this week, while Newfoundland and Labrador Justice Minister John Hogan and other officials from the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador also joined. It was a meeting at Furey’s request. Rich said the Innu leaders were largely repeating their position.

“I told (Furey) that there shouldn’t be any discussions, or there should be no talks about the Upper Churchill, about the 2041 contract, and the Gull Island project [downstream], for various reasons,” he said, citing the outstanding grievances related to Churchill River hydro.

The traditional territory of Innu people, Nitassinan, covers a large part of Labrador, including the area of Churchill Falls. The Innu Nation is a political entity today representing about 3,200 people of the Mushuau Innu First Nation and Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation, based on the Labrador side of the Quebec-Labrador provincial border.

Rich said, right now, there needs to be resolution to the standing legal dispute over rate mitigation on the lower Churchill River development downstream at Muskrat Falls. That far smaller hydro project (824 MW, versus the 5,428 MW capacity at Churchill Falls) went ahead only after a landmark political agreement that included specific financial benefits for the Innu Nation. The Muskrat Falls project ran wildly over budget. The Innu Nation has described the updated arrangements for financing the debt as cutting Innu project revenue by about $1 billion over 50 years. A related lawsuit was filed by the Innu Nation in 2021.

Separately, the Innu Nation wants Hydro Quebec to come to its table to talk more about the harms of Churchill Falls. The Innu Nation is suing the Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corporation (CFLCO, jointly owned by the state utilities in Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador) and Hydro Quebec for $4 billion, stating the companies have been in violation of Aboriginal rights and title and have been “unjustly enriched” by the construction and operation of the larger hydroelectric facility. The suit was filed in October 2020 and remains active.

Another item on the list is the Innu Nation’s land claim. It’s worth recalling, before the agreements for the development of Muskrat Falls on the lower Churchill River, there was a time when the Innu Nation held the stance that no further development would occur on the Churchill River without a conclusion to the land claim process. The Indigenous leadership decided to step back from that hard line. It’s an open question right now as to whether they’ll return to it. In interviews this week, Rich did not make the land claim a requirement to talk of Churchill Falls electricity sales or further development. He only emphasized his message was that the other major concerns stacked up in relation to the Churchill River need to be dealt with.

Mediator coming in

The dispute around the financial details on Muskrat Falls rate mitigation may be the first thing to come to a head. Rich said Furey and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador are being cooperative there and a mediator is being brought in. Fresh negotiations are expected to start in April.

Rich said it’s “very important” to the Innu Nation the issue not drag on.

“I told the premier: once I sit down around the table, I want to walk out with an agreement. It doesn’t matter how many hours it will take. I’m willing to do it. That’s how important this is for the Innu,” the Grand Chief said, adding resolution is needed regardless in order for any other ideas around Churchill River power are to proceed.

The grievance with Hydro Quebec is a different issue.

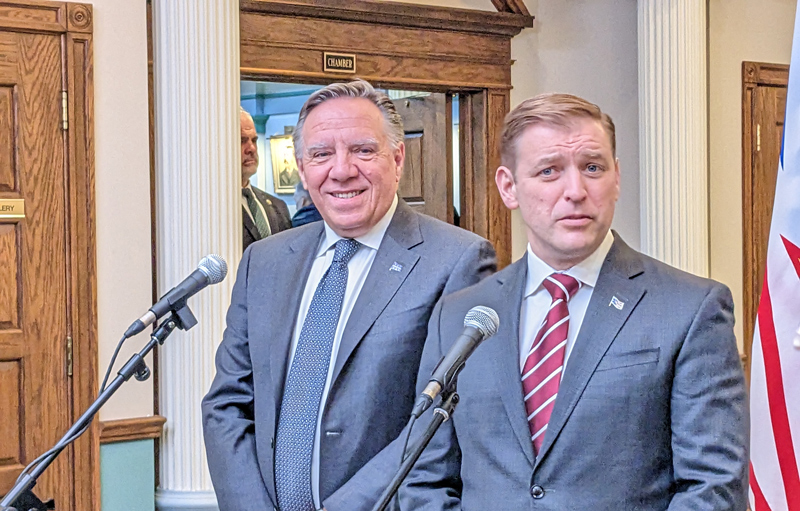

At Confederation Building, after his meeting with Furey, Legault was asked about the Innu Nation and the outstanding issues. “It’s important for me and for Andrew to have discussion with the Innu people and the Indigenous people and we’ll do so together and it’s important for me,” he said.

Pressed on the subject of the ongoing legal action, the question was would he in some way try to encourage state-owned utility Hydro Quebec toward a speedy resolution on its part?

“The people of Hydro Quebec,” Legault responded, “they talk also with Indigenous people and they try to solve these matters.”

Standing beside Legault, Furey said “we” have a redress agreement with the Innu Nation in relation to the Churchill Falls construction, and an Impact and Benefits Agreement (IBA) respecting future hydroelectric development. These are the previously mentioned agreements that allowed the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project to move ahead. “That’s certainly something we would honour,” he told reporters.

The redress on Churchill Falls was part of the Tshash Petapen (“jash-pey-taah-ben” or New Dawn) Agreement, being the previously mentioned landmark accord from 2008 that allowed the Muskrat Falls project to move ahead. The New Dawn was ratified in 2011. It was really a trio of legal arrangements, including one for Churchill Falls redress, a detailed IBA for a Lower Churchill Project development (beginning with Muskrat Falls) and finally a land claim and self-government agreement-in-principal. Notably none of the agreements were with Quebec or Hydro Quebec. Redress payments are paid by the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. And Newfoundland and Labrador, not Quebec or Hydro Quebec, committed to continuing redress payments to the Innu Nation each year after 2041, to an amount tied specifically to existing CFLCO shares and dividends (and as a result potentially affected by any ideas coming out of the ongoing provincial team-to-provincial team talks announced on the tail of the Legault-Furey meeting).

Looking back

Churchill Falls has a deep and painful history, with immense financial losses to Newfoundland and Labrador from the power purchase agreement coming behind the irrevocable change to the environment and lack of respect shown to the Indigenous people when the power facility was created in Labrador.

The construction of the hydroelectric facility was spurred along by different commitments, including a letter of intent in 1966 between Hydro Quebec and CFLCO, being then a subsidiary of the private consortium BRINCO. CFLCO bent itself over a barrel as negotiations on a final contract dragged out. And before any signing in 1969 in Montreal of the “bad deal,” as Legault described the 65-year financial arrangement last week, the landscape in Labrador was being physically remade.

When it came to environmental concerns, well, this wasn’t the Volta River in Ghana, the response went. Canadians weren’t forcibly relocating 80,000 or so people for the sake of hydroelectricity.

“We’re flooding 2,200 square miles and we’re not moving a single, solitary soul,” said engineer Richard Boivin, project manager at Churchill Falls, speaking with the New York Times in 1972, not long before the official event opening of the Churchill Falls plant. In reality, the Smallwood Reservoir, the main reservoir, is over 2,500 square miles (6,527 square kilometres) and larger than Prince Edward Island. It could cover nearly half of Connecticut.

“The ecological disruption is zilch,” Boivin said, with no reported mention of — forget title or rights — Indigenous connection to the land, traditional use, Innu or Inuit people.

Water covered tool caches, sacred sites, burial grounds of the traditionally nomadic Innu. Water was sapped from other areas, diverted from its natural flow by kilometre after kilometre of manmade dyke.

The construction continued. As Philip Smith described in BRINCO: The Story of Churchill Falls (1975), an estimated $946 million in spending would go out in related contracts before first power, with about $19 million going to Newfoundland and Labrador-based suppliers and the rest to Quebec-based suppliers and their subcontractors with — unlike today — no agreement for Indigenous benefits.

New environmental protections

First power from Churchill Falls flowed in 1971, the year Justin Trudeau was born. The event celebrating the plant came in the spring of the following year. While the idea had been around, Environmental Impact Assessment was only formally introduced in Canada the next year, in 1973, under the federal Environmental Assessment and Review Process (EARP). The EARP was considered a planning tool then and simply a reasonable approach for companies to see and address potential construction hurdles early on, to avoid costs down the line. The EARP amounted to more what you’d call guidelines than actual rules.

As public policy expert and Carleton University Professor Emeritus G. Bruce Doern described in his contribution to Canadian Energy Policy and the Struggle for Sustainable Development (2005): “Environmental-energy issues first peaked on the national political-economic agenda in the mid-1970s, when a major inquiry, the Berger Commission, examined the desirability of building a controversial megaproject, the MacKenzie Valley gas pipeline. Because of that commission’s hearings and the sensitivities they raised, the (pipeline) project was put on hold.”

The Berger Commission mentioned Churchill Falls and the later James Bay hydroelectric project in Quebec as other examples of huge developments in what Justice Thomas Berger referred to as “frontier settings.” Unlike many before him who liked to describe Northern Canada as effectively a blank slate, Berger pushed back on the view and emphasized the North “is a homeland too.” On purely environmental concerns, the Commission also offered food for thought with this statement: “Withdrawal of land from any industrial use will be necessary in some instances to preserve wilderness, wildlife species and critical habitat.”

Regulatory requirements around specifically hydroelectric development strengthened little by little. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA) replaced the EARP when it was proclaimed in 1992, setting legal requirements for project assessment. “Sustainable development” became the order of the day. More recently the Impact Assessment Act replaced the CEAA and, barring changes, it would govern new development.

Innu territory

In 1997, then-Quebec premier Lucien Bouchard and Newfoundland and Labrador premier Brian Tobin started down a similar road to what Legault and Furey attempt today, and through backroom and increasingly open negotiations, eventually came to an agreement in principle for a very roughly $10-12 billion Churchill River development (equivalent to $17-20 billion in 2023). Their plan included additions at Churchill Falls, with redirection on the flow of parts of several large rivers in Quebec (including the Romaine River), to add water for the expanded Churchill Falls plant. There was to be an additional development downriver then, at the power prospect known as Gull Island (between Churchill Falls and Muskrat Falls), with investigations into the feasibility of a development at Muskrat Falls.

A great media event was planned, with flights to Churchill Falls for Quebeckers, power players from St. John’s and journalists. On March 9, 1998, it was quite the day, with greetings and photo ops on the tarmac at the Churchill Falls airport, at the edge of the now full-fledged company town. However, out of the airport, a collection of an estimated 100-150 people, headed by Innu community leaders, blocked the way of visitor’s vehicles. There were protest signs. Sheshatshiu band council chief Paul Rich’s voice was heard at one point above the crowd as he yelled: “What you’re about to sign… might as well tear it up, because it’s not going to be proceeding.”

It wasn’t unexpected. The provincial governments had been told by Innu people of the expectation nothing would move forward without their involvement. They’d been warned by federal officials on the same.

Rather than call off the announcement on the day, staffers did some quick maneuvering and, with reliance on a helicopter, private access road and security, eventually got in the announcement of their high-level project plan, regardless of what the crowd outside wanted.

Bouchard and Tobin talked about being committed to “a true partnership with the Innu Nation” (as reiterated in speeches and a Government of Newfoundland and Labrador press release), without any clear statement exactly how that worked.

A New ‘New Dawn’

On more recent consideration of the Churchill River, the Innu Nation opted to appoint a representative, Rick Hendricks, to participate in a panel providing input to the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador on Churchill River electricity. The participation was only with an agreement the province also participate in a side table to assure the Innu rights and revenues from the province’s Churchill Falls redress remain protected.

A crystal-clear statement from Rich and the rest of the Innu Nation leadership dropped into email inboxes as premiers Legault and Furey were in front of reporters.

“Impacts to Innu due to [Lower Churchill hydro, a.k.a. Muskrat Falls] rate mitigation and redress for Churchill Falls must be resolved to the satisfaction of Innu Nation,” it stated.

It added: “Any future deals for development on our territory must have Innu consent. Without that consent, Innu Nation will take all necessary action to prevent any further development.”

As published by La Presse on Saturday, February 25, the day after the Legault-Furey meeting, Innu leaders based on the other side of the Quebec-Labrador have also, separately, called for resolution of their grievances and inclusion in Churchill River talks. The leadership there has collectively stated it is “inconceivable” discussions progress without thought to Churchill Falls redress for “la Grande Nation Innu ‘du Quebec,’” including the individual Innu bands and regional tribal councils on the Quebec side of the provincial border. The published statement from the Indigenous leaders was specifically signed by Uashat mak Mani-utenam chief Mike Mckenzie, Ekuanitshit chief Jean-Charles Piétacho, Essipit chief Martin Dufour, Matimekush Lac-John chief Réal Mckenzie, Mashteuiatsh chief Gilbert Dominique, Nutashkuan chief Réal Téttaut, Unamen Shipu chief Bryan Mark, Pakua Shipi chief Denis Mesténapéo and Pessamit chief Marielle Vachon.

Earlier this year, the leadership of the Innu of Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam launched a similar suit to the Innu Nation over Churchill Falls redress. And Innu people on the Quebec side of the provincial border have similarly, actively, spoken to grievances for decades. As an example, Chief Piétacho, representing the Innu of Ekuanitshit, was one of many people to protest in Churchill Falls against the Bouchard-Tobin announcement. Fast-forward to May 2012, when his personal story was being filed as an affidavit in court, reiterating the travel of Innu people back and forth Nitassinan (across what is now the provincial border). A land use study specific to the Innu of Ekuanitshit found their land use reached Winokapaw Lake, at the Churchill River. “We never stopped asserting our rights and title in Labrador,” he stated. Moving forward to the fall of 2018, Piétacho was asked to testify at a provincial public inquiry in Newfoundland and Labrador, examining the wildly overbudget Muskrat Falls Project hydro development on the Churchill River. He pointed out what he considered failures of the modern-day developers, down to the basics of written communications with Innu communities, often coming as documents written in English, a third language for some people, after Innu-aimun and French. The burden of translation was left on the Indigenous governments.

The Innu people in Quebec were not party to the James Bay Agreement of 1975, allowing for Hydro Quebec developments, but there were benefits agreements with the Innu communities of Ekuanitshit, Nutashkuan, Unamen Shipu and Pakua Shipu settled ahead of the more recent Romaine River hydroelectric project. In 2009, the CBC reported then-Nutashkuan Chief Francois Bellefleur called the Romaine projects “a great opportunity” as a show of commitment to a regional development and the expectation is for further engagement with Innu people.

Apart from the alliance of Innu in Quebec and the Innu Nation interests in Labrador, any Quebec-Newfoundland and Labrador provincial agreements and projects will need to account for the concerns of the Inuit of Nunatsiavut. Their Labrador Inuit Settlement Area reaches to the Eastern side of Lake Melville, while Inuit are active throughout the region, with concern for the Churchill River environment, with intertwined considerations around public health and safety.

There is also the NunatuKavut Community Council (NCC), asserting rights as Inuit of Central and Southern Labrador. The people of NunatuKavut openly opposed the Muskrat Falls construction to start, largely arguing a lack of proper engagement. Relationships with the Newfoundland and Labrador energy corporation improved as the project progressed, as did the Council’s relationship with the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. In 2018, the federal government announced it would begin talks with the Council, to start a Recognition of Indigenous Rights and Self-Determination process, with a memorandum of understanding in 2019. However, NunatuKavut’s position has led to a hornets nest of intergovernmental affairs, given the Innu Nation and Government of Nunatsiavut openly challenged the NCC’s claims both in the press and in court.

On Tuesday morning, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador announced what it’s calling a “discussion team” rather than a negotiating team on Churchill River power. The members are Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro president and CEO Jennifer Williams, past Newfoundland Power president Karl Smith and lawyer with McInnes Cooper Denis Mahoney, who retired from private practice in 2021 and in early 2022 became deputy minister of Justice. Other people will be added from within government to the trio as needed, according to a government statement, “for leading high-level discussions with Hydro Quebec to assess whether there are meaningful opportunities for future negotiations that will ensure the best value from the Churchill Falls plant and the Churchill River for the people of the province.”

A spokesperson for Furey said the meeting with Rich was a chance for, “a good high-level discussion,” adding “of course the conversations will continue.”

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel