Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

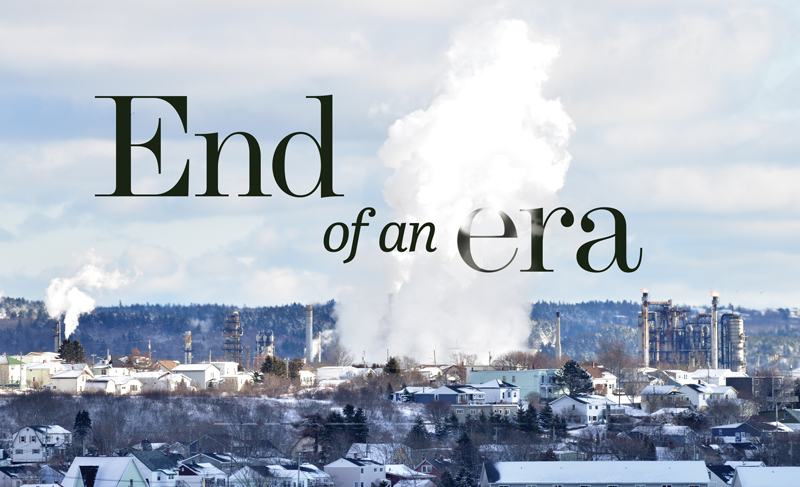

With the possible sale of Irving Oil on the near horizon, Atlantic Canadians may soon have to get used to living in a post-Irving universe. Or not. One way or the other, history will be made

It was impossible to believe, like the “fake news” that occasionally circulates on social media … Climate change a hoax… Covid a government conspiracy… Irving Oil to sell Saint John refinery… Wait, what?

But there it was, in black and white, in a press release on June 7, 2023, under the company’s logo, no less. “Consideration will be given to a new ownership structure, full or partial sale, or a change in the portfolio of our assets, and how we operate them … Today, Irving Oil is announcing that a strategic review of the company is underway.”

Of course, it also said that no decisions had been made about where the strategic review may lead. “As we evaluate our options in the coming months, our focus remains on our team, and continuing to deliver quality products and reliable energy.”

But that didn’t matter. Strategic review … New ownership structure … Full or partial sale. That’s what mattered. Were they serious? After 100 years of corporate existence in New Brunswick—62 of which were spent building and operating what has become Canada’s largest refinery—was Irving Oil actually calling it a day?

What of the thousands of plant and head office jobs in Saint John and beyond? Or the hundreds of businesses across New Brunswick that supply the multi-billion-dollar monolith with goods and services every day? What about the social programs and academic research the Irving family underwrites throughout Atlantic Canada every year?

Indeed, what happened to legendary founder K.C. Irving’s son Arthur’s public pronouncements, time and again, that as the dutiful heir and owner—now 93 years old—he would never leave his province, his region? That he would never allow his business assets and operations to dwindle or be sold to international carpetbaggers who likely wouldn’t give a fig for hard-working Maritimers?

What about (gulp!) us?

“It is … impossible for many Atlantic Canadians not to take great pride in what K.C. and Arthur Irving built.”

—As noted in Donald J. Savoie’s 2020 book, Thanks for the Business

Much like the Bay of Fundy tides, generations of Atlantic Canadians have regarded Irving Oil, and the members of one of the nation’s richest families who built it, as inevitable features of their lives. New Brunswickers, in particular, have felt the heave and heft of that name in their bones—and in their jobs, homes, bank accounts and even in the food on their tables.

Université de Moncton scholar, economic development guru and admitted Irving family friend, Donald Savoie has much to say on the topic. Not in an interview for this story (that was politely declined), but in his 2020 book, Thanks for the Business: K.C. Irving, Arthur Irving, and the Story of Irving Oil.

“Canada’s History Society has identified 10 business titans who helped shape Canada’s economic development,” wrote Savoie. Those storied titans included John Molson, Hart Massey, Sir John Craig Eaton, Harvey Reginald MacMillan, and Kenneth Colin Irving. Unlike many Canadian entrepreneurs, K.C. Irving stayed at home.

Noted Savoie: “It is … impossible for many Atlantic Canadians not to take great pride in what K.C. and Arthur Irving built.”

All of which only made the June announcement stick even more stubbornly in people’s craws. In no time, it seemed, disbelief turned to outrage, fueled by Arthur’s retirement as chairman of the board in October and his executive vice-president daughter Sarah’s quiet withdrawal from active service at about the same time. How dare they?!

The mainstream regional press, for their part, played their roles like out-of-work actors in search of an audition. At least, I did. I had to get an audience.

I wrote to Irving Oil’s CEO Ian Whitcomb in December: “Members of the Irving family have distinguished themselves and their enterprises as pivotal benefactors to non-profits, universities and community organizations in Saint John, New Brunswick and Atlantic Canada for generations … Irving Oil has played an incalculably important role in the regional economy.”

But, why, after all these decades, was Irving Oil’s sole owner, Arthur Irving, even thinking about abandoning his extraordinary sinecure—fabled and crucial in the business, civic and social life of New Brunswick—as one of Canada’s preeminent entrepreneurial success stories and unfailingly reliable job makers?

Did it have to do with the company’s lack of a successor ever since the heir apparent and former CEO, Kenneth Irving (Arthur’s son), retired ostensibly to look after his health in 2010? At about that time, Arthur and his older brother by a year, James Kenneth (J.K.)—kingpin of the diversified forestry conglomerate JD Irving (JDI), the other family-owned business behemoth their dad launched—decided to break up the “empire” and go their separate ways. Was this somehow related? Or was it all about changing federal government policies around carbon taxes and the increasingly untenable oil and gas business in a climate-changing world?

Those weren’t the questions I posed, however. Having read somewhere that the refinery, alone, could fetch between $2–$3 billion, I said, “I’ve received information that suggests that Irving Oil has been negotiating with intent to sell itself, in whole or in part, to TotalEnergies SE, the French multinational integrated energy and petroleum company.”

Was that true?

To which I received the following curt, almost instantaneous, response from company corporate communications specialist, Jack Poirier: “Your information is inaccurate. We continue our strategic review process with no further information to share at this time.”

Also in the no-comment camp were TotalEnergies, J.K. and four Atlantic university presidents whose institutions clearly benefit from an uninterrupted flow of Irving charity.

And yet, the underlying questions remain, still swirling in the miasma of speculation. The fate of a province, even an entire region, feels like it’s hanging in the balance, and it’s hard to dismiss the conviction that something historic is about to happen.

When you climb the open stairs and catwalks that spiral 200 feet or more to the top of Irving Oil’s refinery, you see Saint John the way the Irvings do: A diorama of rooftops and winding streets and broad boulevards, small businesses and arts centers and hospices and God knows what else they and their forebears have built or funded or supported for over a century. It’s a world of successes and setbacks, wins and losses, victories and failures; of chances taken and brass rings grabbed. What it’s not is a world of quitters.

“Quitter” wasn’t a word that made any sense to a young K.C. Irving in the early decades of the 20th Century when he took over the reins of his father’s pulp mill and general store in Boutouche, and opened his own gas station on New Brunswick’s Northumberland Shore. When asked, in later years, what he thought the secret of his success was, he talked about good, old-fashioned horse sense. If it made sense to sell cars, it also made sense to sell the gasoline to run them. If it made sense to sell gasoline, it also made sense to build an oil refinery to produce the gasoline. If it made sense to build a refinery, it also made sense to acquire a shipyard to build the tankers to transport the oil to the refinery. He said, “I like to see the wheels turning”—but that’s about all he said for himself.

He seemed to understand instinctively that if a man does well, he is respected; if he provides jobs, he is admired. And if he minds his business and lets other people mind theirs, he is a native son and welcome to his privacy. He believed that with that attitude, the right man with the right idea could go far in this economically unpromising corner of Canada. And far he went.

By the time he died in 1992, his vast holdings were nothing short of byzantine in complexity; nothing shy of imperial in value. No outsider was ever able to crack the actual ownership structure, let alone its net worth. At K.C.’s peak sometime in the late ‘80s, estimates routinely ran into the hundreds of companies generating, altogether, at least a couple of billion dollars in annual sales.

In Saint John, there was the oil refinery. But there, also, was the first deep-water oil terminal in the Western Hemisphere, a shipyard and a drydock. There—and across New Brunswick, the Maritimes and Maine—were hundreds of service stations; bus and transport companies; office towers and apartment buildings; convenience stores and laundromats. Farther north, through JDI, the name Irving meant millions of acres of choice timberland; pulp and paper plants; mines and smelting companies; trucking companies and frozen-food operations. JDI, alone, controlled about a tenth of the province’s land, employed a twelfth of its workers, owned every English language newspaper but one, and most radio and television stations.

In 1987, when the Globe and Mail, in its dubious wisdom, decided to send me, then a 26-year-old business reporter in the Toronto office, down to Saint John to try to figure out all this stuff, I managed to score an interview with Peter Glennie, a lawyer who had spent years poking away at his own Irving company flow chart. A dryly affable man with a ripe appreciation for irony, he told me, “Lookit … The people in New Brunswick aren’t all that interested in these matters—what he owns, what he’s worth—as long as he doesn’t take his business elsewhere.”

That seemed to be K.C.’s unspoken promise to the province, passed down through his three sons—Arthur, J.K. and John (who ran the real estate end of the business until his death in 2010)—to whom he entrusted his “empire.” According to Savoie, that commitment to home is still profoundly important to Arthur. “Arthur Irving is a deeply committed Maritimer … as K.C. was … always on the lookout to expand his business and generate economic development,” he wrote in Thanks for the Business.

As for the refinery, “I can’t see them packing it up and moving. No, I don’t see that happening.”

—Donna Reardon, Mayor, Saint John

Some notable New Brunswickers tend to agree. “A lot of big companies have their owners living in exotic places,” said Saint John Mayor Donna Reardon, who’s gotten to know most of the extended Irving clan since she was first elected to council in 2012. “A lot of the family live in Saint John and invest in Saint John—whether it’s parks or the food bank. And you can see that every day… I don’t know anything about any long-term strategic plans at Irving Oil, but I would hope that I have the sort of relationship with the administrations of the Irving companies such that if something were going to happen tomorrow, I would get a heads-up.”

Bob Manning, a wealth management advisor who works at Owen MacFadyen Group in Saint John and who was chair of Enterprise Saint John, the city’s economic development agency, for two years in the late aughts, is even more emphatic. “When I was involved heavily with economic development, I got to know all the entities quite well. They are New Brunswickers, born and bred. Their headquarters are here. Their full intent is to stay here through the years and make this the best possible region, the best possible province, to live in. That means workplace, cultural life, recreational life, social life … everything. They’re not here for the short term. They are here for the long term.”

Regarding the publicly announced strategic review, he said, “Clearly, they are going through a transition, asking questions … Who are we? Where are we at today and what sort of structure do we need to have in the future?”

None of the above observations are anything anyone can take to the bank. The Irvings are, after all, fiercely closed-mouth about their affairs. And maybe the optimists, ignorant of the deeper family dynamic, are wrong.

Who really knows how Arthur truly feels about the split between Irving Oil and JDI. Did it leave him feeling high and dry and alone?

What about Kenneth, who left in a nearly impenetrable cloud of personal troubles and professional grievances, telling the Wall Street Journal in 2014 that “there is a complexity that comes from being in a family business” that’s hard for outsiders to understand.

And what about the existential threat that worries everyone involved in the oil and gas sector if not the whole economy: climate change or, more precisely, the politics of climate change? Certainly, Louis Léger, former chief of staff to New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs thinks it could spike any hope for Irving Oil as it’s currently configured. “That refinery wasn’t built because the Irvings were sitting on an oil well,” he said. “It was built on brains and logistics, one of which is its proximity to the New England market. That, and the ability to bring in crude from around the world at good price. But now … the carbon [pricing system] … the clean fuel standards. All the polices of the Government of Canada at the moment, adding huge costs, are designed to almost kill Irving Oil. The refinery will now need constant investment and reinvestment to survive, let alone, thrive.”

Maybe all of this is enough to compel a man—even one as tough and resourceful as Arthur Irving—to finally throw up his hands and get out while the getting is good.

Several knowledgeable New Brunswick sources told me the fact that Irving Oil even announced its strategic review is revealing. Said one, who was only willing to speak on condition of anonymity: “There’s absolutely no reason for a [private company] to do that unless there was a possibility that [a sale] would show up in a public [buyer] company’s filing. And if it did, some intrepid journalist would find it and announce it to the world. So, it’s pretty clear that [Irving Oil] wanted to get out in front of this.”

One big concern, this source said, would be the knock-on effects of a non-Atlantic Canadian company calling the shots. “The issue is that if Exxon takes over, or one of the other refiners, they already have operations in Canada. So, you would think they’d just [incorporate] Irving Oil into those.”

“A lot of people here still don’t associate Irving Oil, JDI and McCain Foods as vital to their well-being and success. But these companies were basically the economic development projects after World War II that created a sustainable economy with jobs and good incomes.”

—Herb Emery, Vaughn Chair in Regional Economics, University of New Brunswick

All of which makes Herb Emery—the Vaughn Chair in Regional Economics and deputy chair of the University of New Brunswick’s political science department—cringe. He thinks that if Irving Oil were to sell to the highest bidder, the impact would be far more serious, widespread and durable than most New Brunswickers think.

“A lot of people here still don’t associate Irving Oil, JDI and McCain Foods as vital to their well-being and success,” he said. “But these companies were basically the economic development projects after World War II that created a sustainable economy with jobs and good incomes.”

Since the Great Recession of 2008, “New Brunswickers have shifted back to relying on income sources that aren’t generated within the province, notably federal government transfers. As a consequence, you have industries here that other lagging regions would kill to have around—like Thunder Bay, Sudbury or even Come-By-Chance, with its refinery.”

Emery’s point is that once these industries go, their loss impacts a city, a province, even an entire region in direct proportion to their former significance. That’s when they’re missed; when it’s too late.

Said David Campbell, owner of Moncton-based economic research firm Jupia Consultants and former chief economist of New Brunswick (2015-18): “Remember NB Tel in Saint John, which lost a net of more than 1,000 high-paying jobs in the telecommunications sector after the Bell takeover [in 1999]. That didn’t include the supply chain; all the PR and marketing firms … Right now, in addition to all the other supply chain activity, Irving Oil’s head office, alone, probably represents $100 million of direct spending a year.”

Irving Oil’s various boilerplates report that the refinery produces 320,000 barrels per day (bpd) and runs more than 900 fuelling stations and distribution channels across eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. To do this it employs roughly 3,000 people. It also oper-ates Ireland’s only refinery (75,000 bpd) in the village of Whitegate.

In Thanks for the Business, Savoie crunches those numbers. “The regional economic development literature explores how to calculate the multiplier factor when new jobs are created [or] when assessing the impact of existing jobs,” he wrote. “There’s some debate around the size or scope of the multipliers, but I’m on safe ground in suggesting a multiplier of 2.5 for Irving Oil. Indeed, one economist who has undertaken a number of studies in this area tells me that if anything I have likely underestimated its importance. Irving Oil [refinery and head office] directly employs about 3,000 people, while an approximately equal number come to work every day at [all] Irving Oil operations. The 6,000 jobs at Irving Oil (not including those in Ireland) multiplied by 2.5, translate into 15,000 other jobs.”

Meanwhile, according to Statistics Canada, in 2022, the market value of all imports to New Brunswick was about $18.1 billion, of which about $12 billion was crude destined for Irving Oil’s refinery. That same year, exports of oil and gas products from the refinery to the rest of the world amounted to roughly $12 billion, more than half the value of the province’s total $19 billion in outgoing trade.

Is it surprising, then, that oil and gas comprise 90 per cent of the Port of Saint John’s annual tonnage? “The Irving Oil refinery is unique in Canada, as 80 per cent of its product is exported,” Emery said. “So, if they get rid of the export arm, it [would be] a much smaller operation, serving just a regional market.”

Put it this way: “You don’t lose a major industry that has taken decades to make successful, and just go out and get another one off the rack. This is the kind of economic scarring that leaves regions behind permanently.”

Think Flint, Michigan, following the exodus of U.S. auto makers in the 1970s and ‘80s, and you get the picture.

Then again, maybe not. Many New Brunswickers insist that Arthur Irving and his clan are in it—New Brunswick, the Maritimes, Atlantic Canada—for the long haul simply because the evidence points in that direction.

Sure, Arthur must have been troubled by the succession debacle. Still, he’s had a decade or more to adjust—more than enough time to prepare his C-suite to handle whatever executive challenges that funnel through his HR pipeline.

As for the “big split” with J.K., if there was a time when soaring fortunes at one of the companies compensated for dwindling opportunities at the other, that time was long ago. Even before the breakup, both firms operated independently of one another; each as solid as Gibraltar.

(For the record, no one in New Brunswick believes for a second that JDI is going anywhere. Said Campbell: “What are you going to do? Move the trees?”)

Meanwhile, though Government of Canada climate change policies may be loading up huge costs, they are loading them up on everyone. At some point, industry performance expectations adjust, margins follow and the playing field levels again for all. It’s true that Irving Oil would need to constantly invest “and reinvest” in innovation to stay alive, but that’s nothing new. In 2000, people said that spending a billion bucks on a catalytic cracker for the refinery to produce lighter, more varied and more valuable petroleum products was nuts. People were wrong.

In fact, on the continuous and onerous effort to deploy new technology and processes to stay on top of the green curve, Irving Oil’s 2022 sustainability report is remarkably chipper.

They’ve invested, they say, “in a hydrogen electrolyzer, marking the first pathway to green hydrogen for customers in the Atlantic region [and] in transforming waste into renewable natural gas to support decarbonization of our operations.” They say they’ve also “forged a partnership with Saint John Energy to provide fully decarbonized electricity to more than 30 Irving Oil properties in Saint John.” They’ve even “unveiled Irving-branded electric vehicle chargers as part of (their) EV network—the largest EV network in Atlantic Canada—and launched a third solar-powered retail site, now with locations in Salisbury and Quispamsis in New Brunswick, and Pembroke, Massachusetts.”

Those are just the achievements. Here are the goals: Thirty per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and “steps towards achieving” a net-zero goal by 2050.

“True to the values that have guided our company for nearly 100 years, we are committed to being leading and engaged partners in reducing emissions in our industry and in our communities as we all work toward a lower carbon future. Our work positions Irving Oil for long-term resiliency and growth through the energy transition process, while maintaining a strong, reliable and safe core business that delivers value to our customers and the communities we call home. We are on a continuous journey of sustainable development,” noted the inhouse sustainability report.

Of course, these are only words. Yet, it’s hard to regard Irving Oil’s spiffy, new LEED-certified headquarters in the centre of Saint John—built for a cool $88 million (est.) between 2016 and 2019—as mere window-dressing. Donald Savoie doesn’t.

“Irving Oil does not make major decisions lightly … No expense was spared in erecting the state-of-the-art building,” he wrote in Thanks for the Business. “I appreciate the building’s elegance; however, it holds a far more important message for me. In committing the funds to erect an 11-storey building, the company established a mark for years to come: Irving Oil’s head office is in Saint John to stay for the long term.”

All of which makes optimists think there’s a fair bit of daylight between the words “full” and “partial sale”. Even some of the pessimists get the point.

“Say a big firm like TotalEnergies SE, or whoever buys Irving Oil, keeps the head office in Saint John, continues to invest in the refinery and makes it the last one standing in Canada so it stays around 30 years,” one industry source told me. “Most of the gas goes to New England [because] Americans are less interested in EVs and energy transition … Now, if you look at [Total’s] corporate plan, they are also investing heavily in green energy … If they get a foothold in Canada, in Saint John, maybe they start investing new cash here. So, then, the money they paid for Irving Oil—or at least some of it—gets reinvested in New Brunswick in new ventures.”

For her part, Saint John Mayor Donna Reardon prefers to deal in facts. She doesn’t “know anything” about TotalEnergies or whether it may be a suitor in any sale—partial or otherwise—of Irving Oil. She did, however, enjoy hosting a delegation from the Brussels-based Don Bosco network of private schools (famous for catering to the educational needs of far-flung French business executives and their families) last September. As Canada’s only officially bilingual province, New Brunswick offers many centres of Francophone cultural and linguistic excellence. Saint John isn’t one of them.

Reardon said, “What they liked about us is that we have that small, inner city that attracts people. They loved the Victorian architecture here. They said they felt like it was a very European city, but on a smaller scale … It was interesting … I still don’t know what their impetus was.”

“We had been in the midst of trying to raise the remainder of the money that we needed to build what was going to be the best emergency department in North America, when the Irvings asked us to come on a call with them… Then, all of sudden, Arthur leans in and said, ‘Jen, can I just say something?… ‘Would you accept a donation of $6 million from us to kickstart your campaign?’ I actually started to cry … I never cry.”

—Jennifer Gillivan, president, IWK Foundation (Photo: Cooked Photography)

It was 2022 and Jennifer Gillivan, president of the IWK Foundation in Halifax—the preeminent fundraising organization for children and women’s healthcare in the Maritimes, and one of the largest charities of its kind in Canada—sat in her office preparing to sign into the zoom call that Arthur Irving, his wife Sandra and their daughter Sarah had arranged days before. This wasn’t Gillivan’s first rodeo. She’d spent the past 10 years schmoozing and cajoling the region’s rich and powerful, including her hosts, who she considered friends. But she was nervous. This meeting felt different.

“We had been in the midst of trying to raise the remainder of the money that we needed to build what was going to be the best emergency department in North America, when the Irvings asked us to come on a call with them,” she recalls. “So, here I was with my VP of development and VP of philanthropy launching into a massive sales pitch, as you do, you know … Then, all of sudden, Arthur leans in and said, ‘Jen, can I just say something?’ And I said, ‘Sure’, but I was thinking, ‘Oh God, he’s going to ask me a question I don’t know the answer to.’ Instead, he said, ‘Would you accept a donation of $6 million from us to kickstart your campaign?’ I actually started to cry … I never cry.”

Gillivan says the only reason why Arthur let her go public about the gift was that “he felt it would inspire others to give … And it has. We are well on our way to finishing our goal … It’s just the way he did it. It was so genuine.”

Indeed, said Camille Thériault, CEO of UNI Financial Corporation in Caraquet, N.B., and former premier of New Brunswick, “They don’t talk about a lot of the things that they do privately, but they are way more pivotal than you think.”

Savoie agrees. “Often, Arthur and Sandra, the (Irving) Family Foundation, and Irving Oil have not given a full public hearing of their contributions,” he wrote in Thanks for the Business. “Harvey Gilmore [once] underlined this issue when he said that one of his most frustrating experiences as director of development at Acadia was that he was not allowed to talk about Arthur Irving’s contributions to the university … The question is, in their absence, who would have stepped in to make the same contributions?”

Thériault may share, with others, a gloomy view of the province’s economy should the company become a corporate vassal of some international player, but he’s not convinced that’s the only, or even leading, option on the table. “Arthur is getting up there in age, and I think the most normal thing for a successful business person to do is weigh whatever alternatives are out there,” he said. “On the other hand, you could go to every community in New Brunswick over the past 50 years and you will definitely see how Irving Oil has participated in making these communities better by their generosity.

That’s a point both pessimists and optimists make about all the possible futures now in play; a lifelong commitment to the places and people that helped the Irving family build a business empire is just not something they will, or even can, quit.

Their industry, even its players, may change. But at the core of it all, they’ll remain here, in both flesh and spirit, because here is where they can still touch all the successes and setbacks, wins and losses, victories and failures—all the chances they ever took, and all the brass rings they ever grabbed. Here, home, is where the real possibilities still live.

“I think,” said Gillivan, “this family has been on the tightrope way up high, and we’ve all been watching them for a long time, seeing if they’ll make it to the other end or if they’ll fall. And every time we do that, it gives us a chance to think about how we’re doing … you know? These people may be billionaires, but they face the same questions we all do. They all end up in the same place we do. The question for us is: Did we make an impact? Did we do something extraordinary? What if we all suddenly did do just that, like the Irvings?”

Becoming more like them in a province, a region, a world that they helped create, but soon may no longer dominate? Now, that would be historic.

Similar Articles:

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel

There is no doubt the possible sale or partial sale of Irving Oil has dominated local business discussion here in Saint John.

While your article ‘End of an Era’ provided the broad brush strokes to this story, I feel the fact such a discussion in this regard is even happening is due to one thing.

Lack of family leadership moving forward.

The grim reality is that – within Irving Oil- the lack of an Irving successor to Arthur Irving is the problem.

While Kenneth Irving’s health challenges have been well chronicled, his vision for Irving Oil’s future did not align with that of his father.

Kenneth detailed the ‘complexity’ of being in a family business as well as inside Irving family life in a revealing and honest feature article in ‘The Globe & Mail in late January 2017.

Kenneth wanted Irving Oil to branch out into alternative energy sources: tidal, wind , and solar power.

His father’s now famous quote:

‘We sell oil, that’s what we do.’

This apparent divide was never bridged and it has brought Irving Oil to where it is today.

If you had suggested 20 years ago that a day would come when Irving Oil would be sold, people would have thought you were crazy.

It would never happen.

But, here we are.

Should Irving Oil be sold( in whole or in part), the company would have lasted two generations under family leadership.

With the Irving family 3 way split happening now well over a decade ago, it is only the Irving Oil segment with family leadership problems.

The future looks much different for the other Irving ‘segments’.

JDI with pulp&paper; shipbuilding; frozen food products; trucking; offshore support ; and paper products has long range leadership intact within the sections of the Irving family involved.

Indeed, beyond Arthur’s brother , JK Irving, his two sons James and Robert and their children are positioned to lead JDI for decades.

Jack Irving’s family(headed by his son, John) has leadership in place as well.

Under the name Ocean Capital Investments this section of the Irving family is involved in real estate; engineering services; hardware; broadcasting ; structural steel and concrete.

Ocean Capital Investments have businesses throughout Atlantic Canada extending into Central Ontario and Western Canada.

In the end, they say it is rare for a family business to last further than 4 generations.

While the future of Irving Oil appears somewhat uncertain, it is clear the company’s leadership will undergo some changes – large or small.

will our pensions be safe