Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

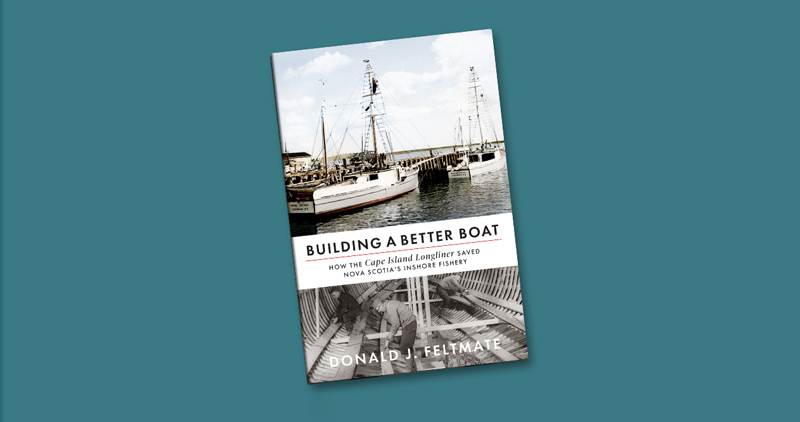

Traditional industries can be as innovative as any of the latest and greatest technology advances. Author Donald Feltmate makes the case for one industry in particular in Building a Better Boat: How the Cape Island Longliner Saved Nova Scotia’s Inshore Fishery.

It wasn’t “just a fishing boat,” Feltmate explains; he believes the local longliner was key to saving many small, Maritime communities from becoming ghost towns in the wake of the Great Depression and war.

“The economic impact that these vessels had on the life of every Nova Scotian between 1950 and 1985 has hitherto gone virtually unnoticed,” he argues.

Neither a schooner nor trawler, the Cape Island longliner evolved to meet specific needs. As Feltmate explains, the boats were designed with input from fish harvesters, built locally, motorized and could accommodate small-boat fishermen who needed to working further from shore—all while being manageable both mechanically and financially.

Crucially, he says, they were part of a multi-generational effort to give a new foundation to the “shore” (ie. inshore) fishery. That push, as he describes it, dates back to at least the 1920s.

“This (book) tells how these people, common workers, broke their backs and risked a lot to be able to save what started out as their industry (…) and the hurdles they had to overcome,” he told Atlantic Business Magazine.

“This (book) tells how these people, common workers, broke their backs and risked a lot to be able to save what started out as their industry (…) and the hurdles they had to overcome.”

Essential Maritime history

Feltmate was born in Port Morien on Cape Breton and has family ties to the shore fishery. He now lives in Sunken Lake, N.S. Prior to this latest release, he produced a pictoral history of the Cape Island-type longliner for the Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic. He felt there were more details to be uncovered.

Here, he describes the poverty that existed among thousands of shore fishers and their families after the First World War. He writes about individual fish harvesters who were largely “at the mercy” of large companies, with challenging conditions and increasing competition at sea thrown on top.

“They were masters of their craft, but they weren’t versed in the business side,” Feltmate said, talking about the steps fish harvesters took to change their standing in industry and financial success over several decades.

Into the 1940s, he suggested, there was too often “a false impression” of the Nova Scotian fisheries doing well. Those false impression were based on formal reports that he says focused on too few ports. For instance, he describes how, at one point, about 10 per cent of fish harvesters in Nova Scotia were landing over two-thirds of all flatfish and groundfish at just four ports. It was a very different story for decades for the many smaller and quieter ports around the province.

The less fortunate ports were not as far along in their recovery post-Depression and not as well equipped for handling fish and lacked other essentials needed to compete. At the time, capital to improve things was still hard to come by.

“The need for change and better equipment was brought to the attention of and acknowledged by both levels of government as early as 1925, yet it took another 20 years, two Royal Commissions, and the aftermath of another world conflict to finally see some measurable progress toward the (shore) fishers being provided with much-needed financial support,” Feltmate argues.

Change on land

In the book, he reviews pivotal moments tied to the inshore through the years, including the “Canso incident,” a peaceful protest by fish harvesters in Canso in 1927 that led to a Royal Commission investigation and the development of community-rooted co-operatives. The formation of co-operatives, including eventually the organization known as the United Maritime Fishermen (UMF), as he summarizes at one point in the book, “did not sit well” with large processors and buyers.

The collectives began to see individuals sacrificing limited, individual profits for bulk purchases of supplies like netting and hooks, building momentum for larger infrastructure like the addition of processing facilities.

Feltmate’s detailed work is grounded by finer details, like a photo of the Guysborough Fishermen’s Co-operative processing plant in Whitehead, first opened in 1946, employing about 20 people in the rural area processing groundfish and even blueberries after the fishing season. It added a little more revenue to the county (Feltmate notes the location is still in use today as a lobster pound).

This is where the innovation of the Cape Island-type longliner comes in. Apart from building new associations and infrastructure onshore, inshore fish harvesters also had to deal with increasing numbers of large steam trawlers or “draggers”, together with declining catch rates in their usual fishing grounds.

“Fishers realized that to further advance their financial gains they required a vessel that could remain on the grounds for longer periods than just the day fishing, fish longer into the fall and possibly the winter, and be affordable,” Feltmate states.

They needed boats to allow them greater reach and boats they could afford, develop quickly and be comfortable working with. Into the 1950s, many of the co-ops would come to be served by the new Cape Island-type longliners.

“Fishers realized … they required a vessel that could remain on the grounds for longer periods than just the day fishing, fish longer into the fall and possibly the winter, and be affordable.”

Innovation for the sea

Individual boatbuilders and shipyards in Nova Scotia had an international reputation dating back to the early 19th century. Even on some of the most famous ships in the world, including large schooners like the original Bluenose, master boatbuilders worked by conventions, without being governed by formalized construction standards and blueprints. Feltmate retells some of that history.

Heading into development of the Cape Island-type longliner for the inshore fisheries, he explains, things were changing. Change was tied to federal financial support as well as seeking means to review and assess builds. But the rapid movement to standardization also created delays.

Thankfully, fish harvesters were in a better financial position compared to immediately post-Depression. The Nova Scotia Fishermen’s Loan Board was founded in 1936 and Feltmate says it provided help to individual fishers by the mid-to-late ‘40s. Specific to boatbuilding, a Federal Fishing Vessel Construction Assistance Program was introduced for Western Canada but then came East, initially targeted to deep sea fleets. When they did make changes to assist the inshore, they weren’t always thinking of individual harvesters and what they had to work with.

“During the period that followed the Second World War, the shore fishers watched as newer and larger vessels were being built for fish processors using provincial and federal funding while they were not able to individually qualify for similar programs,” he writes.

Hurdles were easily put up and less easily overcome. With the move to standardization for builders in the 1940s, the federal government demanded designs be approved by a naval architect. There were only two in Nova Scotia at the time, Feltmate points out. But smaller builders and shore harvesters persevered, pressing forward with demands for legislative changes that would see more supportive funding flowing for the boats fish harvesters wanted.

A class of vessel describes how it will be used (think aircraft carrier, cargo ship) whereas a type of vessel is about its construction specifics and design relative to that use. The wooden Cape Island-type longliners were not all exactly the same, but the essentials were there for mid-range fishing. Some of the boats could have a little more room for ice, or a bigger pilot house within the standard specifications, but the pilot house tended to be enclosed, offering shelter that open boats didn’t have, and more bunk space if needed. The newer boats could also accommodate a diesel engine rather than rely on sail and oar. They commonly offered a sheltered area for dressing fish. And they had enough fuel space to enable travel to a greater distance from shore, with the capacity to stay out overnight if necessary.

The first Cape-Island type longliner launched in 1947. Smaller shipyards could handle the builds and, by the mid-1950s, they were under construction all around Nova Scotia. Feltmate describes the benefits to smaller builders like Dover Boat Works, that complemented the larger yards such as Clarence Heisler yard, Harley S. Cox and Sons Ltd., Kenneth McAlpine & Sons Yard, John Maclean & Sons Ltd. and more. Construction of the vessels peaked between 1955 and 1959.

“The expansion of the Maritime fishery brought with it the largest period of vessel construction seen in Nova Scotia since Confederation,” he writes.

“The expansion of the Maritime fishery brought with it the largest period of vessel construction seen in Nova Scotia since Confederation.”

In addition to construction work, the boats were put to successful use in gathering and bringing fish to local processors, buyers and secondary sellers.

The number of new builds dropped off into the 1960s. Feltmate said this was partly because it became more profitable for shipyards to build large draggers, with smaller builders going by the wayside. There was also a drop in groundfish availability, making any build a tougher value proposition.

By the late 1950s, “everybody was scrounging to get fish,” he said, condemning the increased use of trawlers and draggers as a major contributor to declines in groundfish stock. That has challenged the industry in the decades from then to now. But fundamentally, he tells Atlantic Business, without several decades of this particular innovation, “you wouldn’t see a lot of these small communities” once dependent on the fisheries, increasingly diversified in modern Nova Scotia.

More Book Reports:

In Book Report, Atlantic Business Magazine is highlighting non-fiction focused on Atlantic Canada and Atlantic Canadians, and from Atlantic Canadian publishers. These short pieces will offer details from upcoming business biographies, Q&As on new releases and in some cases fresh commentary from non-fiction authors on the subjects of their published works.

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel