Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador is taking a closer look at the potential for long-term storage of carbon dioxide offshore Newfoundland and Labrador. The province launched an Innovation Challenge last week, backed by $6 million in public money. There is interest within the government in moving forward locally focused R&D and exploring carbon dioxide storage, with some elected members believing storage could become a whole new local industry.

The idea of capturing and concentrating carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, shipping them to be stored underground, is not new globally. It does raise questions locally around potential public costs and credits involved, private sector benefits and viability.

The new, provincial R&D program isn’t about launching full-scale storage projects. It’s a far more introductory level of work. That said, for the mix of politicians, bureaucrats and researchers looking to forge ahead, it’s also landing in an uncomfortable crossover of (1) ongoing debates related to offshore oil and the oil industry (and corporations that have been reporting historic profits) and (2) costly actions needed for greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

A starting question here might be why the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador has come out now with its new contributions on carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) R&D. A brief but formal launch of the CCUS Innovation Challenge was held at the Bruneau Centre for Research and Innovation at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador’s St. John’s campus on Tuesday, Oct. 17. The actual idea for publicly backed R&D started to germinate back with MHA Perry Trimper, who attended the launch.

With a background in environmental science, including studies tied to resource development in Labrador, Trimper has long expressed a personal interest in the challenges of climate change. First elected to the Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly in 2015 as representative for the district of Lake Melville, he also served in the years since as the province’s Minister of Environment and Climate Change and then as a Special Advisor to the Premier on Climate Change, the latter appointment ending in October 2020.

“We’ve got (…) an oil and gas industry that is very important for this economy and as they move more and more in the direction of doing what they can to reduce their footprint, here’s a golden opportunity.”

—Perry Trimper, MHA Lake Melville

At the new R&D challenge launch, he told reporters he sees an opportunity for reduction of the global and local carbon footprint through offshore CO2 storage. He took the idea of taking provincial action to Premier Andrew Furey “about a year ago,” he said. That would have been around the time he rejoined Furey and the Liberal caucus, having left the Liberals back in November 2020 to sit as an Independent for a time. He says the premier was receptive. Trimper contributed to work in government on the idea, then to now, ultimately coming to the R&D program.

Trimper was clear that he sees a possible win-win scenario with carbon capture locally, beginning with a start on seeing in more detail the real potential for CO2 emissions to be captured, shipped and injected into the ground, as well as the potential for CCUS to reduce final emissions from existing offshore oil producers.

“We’ve got (…) an oil and gas industry that is very important for this economy and as they move more and more in the direction of doing what they can to reduce their footprint, here’s a golden opportunity,” he said.

The province is putting up $6 million, to be split between two different R&D project streams.

The first stream offers $3 million for proposed projects focused on CCUS for decarbonization of ongoing oil production. The second $3 million total is available for projects involving study of the feasibility for a regional CCUS hub to be based in the province (As a note on naming: CCUS not involving re-use of the CO2 and just storage is often referred to as just CCS, though some people and even policymakers sometimes use CCUS as a catch-all and the true nature here may depend on the proposal).

The expectation is for applications from partnerships of the private sector and post-secondary institutions. No joint venture team will get a full $3 million in provincial funding. The teams are being asked to file their individual applications with proposals in the $1.5 million to $3 million range, and for one of the two streams. It means, depending on the final applications, the government can help fund two to four projects in all.

The government is covering only up to half of any eligible project’s cost, so the hope is the public money can be leveraged for another $6 million at least from the private sector, for at least a $12 million in total spend on CCUS-related studies in the next few years. Proponent teams have to submit project ideas they can complete within two years of any funding approval. The proposals for both streams of R&D will be reviewed by a panel of experts including representatives from the provincial Department of Innovation, Energy and Technology, the provincial Department of Environment and Climate Change and the National Research Council of Canada’s Industrial Research Assistance Program.

“It certainly feels as though we’re at the beginning of something great for our offshore and for our province,” said Energy NL CEO Charlene Johnson, at the R&D challenge launch event, describing “significant potential in CCUS.” Separate from the province’s funds, a three-way collaboration of industry associations Energy NL and econext, and the province’s wholly owned oil and gas corporation is working on a “Net Zero Project,” set to look at available infrastructure offshore and the feasibility of use of the infrastructure for applications like long-term carbon storage. A proposal there is in a federal review process.

Like Johnson, econext CEO Kieran Hanley was also on hand for the province’s R&D challenge launch on carbon storage. They were joined MUN president Neil Bose, chair of the board of regents Glenn Barnes, current provincial Minister of Environment and Climate Change Bernard Davis, Minister of Industry, Energy and Technology Andrew Parsons and Furey.

The premier was asked why the province would spend $6 million on the related R&D work, being equivalent for context to twice the top-up he’d announced the day before for emergency Newfoundland and Labrador Housing renovations. Why spend public money instead of calling for it from, say, the oil companies?

“This is not a subsidy to oil companies. This is an incentive to academics and private industry to come together,” he said.

ABM pressed on the fact there were early consultations with offshore oil and gas industry operators about the R&D funding (not to mention the fact a stream of the R&D challenge is specific to the oil and gas industry). Isn’t this funding not ultimately targeted to oil companies?

“Not necessarily,” the premier replied, saying the program is intended as an incentive for R&D.

“This is not a subsidy to oil companies.”

—N.L. Premier Andrew Furey

At the event, he and others highlighted the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) plans for reaching global goals on emissions reductions, where carbon capture and storage play a role. The IEA has stated plans for adding new carbon storage globally are not on target for its Sustainable Development Scenario, lagging behind even planning for just carbon capture at industrial sites. It risks heavy industrial companies having carbon capture in place, waiting on final storage.

“This means that there will be a global demand for carbon storage solutions and Newfoundland and Labrador will play a key role in that,” Furey said.

Furey pointed to the experience of local industry offshore as a result of oil and gas work as an asset. He said things like the extensive data from offshore seismic and other testing for exploration and production will help with CCUS. For example, in identifying and evaluating the underground reservoirs where CO2 might be injected.

Furey and provincial officials at the launch also mentioned the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), saying the panel concluded reaching global climate goals will require CCUS. Yet, there was no mention of related warnings like the one issued by IPCC Chair Hoesung Lee in June who, as the Guardian reported, warned against overreliance on carbon capture in climate change response.

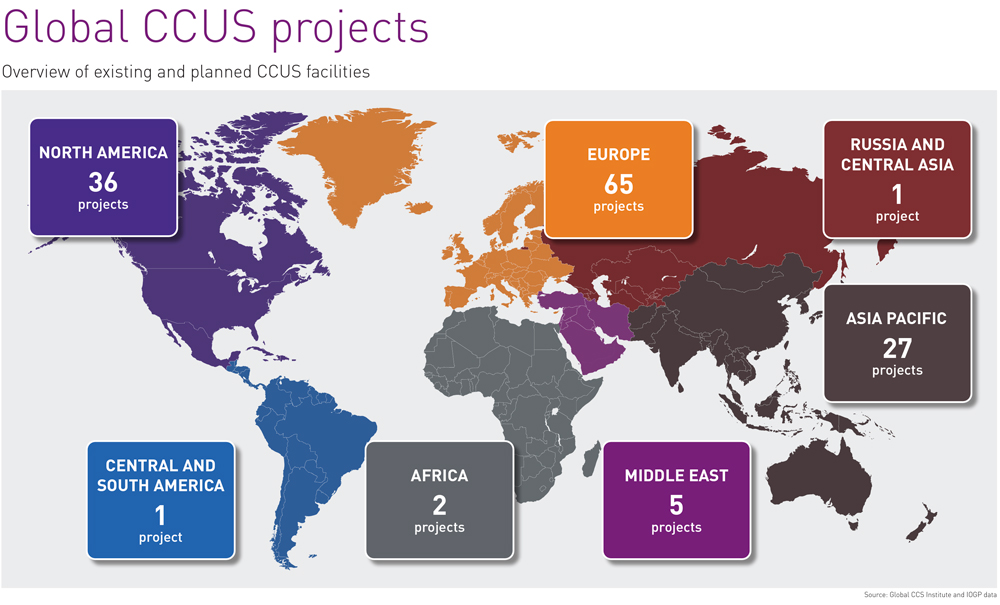

At one point the premier referred to CCUS as “new technology.” However, the same corporations involved in oil and gas exploration and production offshore Newfoundland and Labrador through the years also have decades of experience with different variations of CCUS projects. There have been failures. But the companies are also partnered in what today are considered some of the most promising projects globally.

During the event, there were general references made to CCUS projects being in place in Western Canada, and internationally in places like Norway. In terms of Canada, reference was made in information provided to reporters by officials to the Alberta Carbon Trunk Line, the Quest project in Alberta, the Boundary Dam in Saskatchewan and Weyburn-Midale CO2 project in Saskatchewan as examples of CCUS projects. Written briefing material described how Canada is “already a leader with four, large-scale CCUS projects,” though with nothing in the same on timelines, goals, ownership, results to date. The projects are all very different.

Consider the Weyburn project in Saskatchewan. There was oil production in the area dating back to the 1950s. In the late 1990s PanCanadian Petroleum and 36 partners announced a plan for an enhanced oil recovery (EOR) project that today would fall under the umbrella of CCUS, pumping CO2 captured in North Dakota over into the ground in Saskatchewan to help get more oil out. There were some changes through the years. In more recent years, Cenovus (also offshore Newfoundland and Labrador) was involved, leading operations on behalf of more than 20 partners, before selling its stake in 2017.

The Quest CCS project in Alberta, operated by Shell Canada on behalf of the Athabasca Oil Sands Project, captures emissions from a bitumen processing facility near Edmonton. It opened in 2015 but fell short early on of hitting a goal of a million tonnes of stored CO2 a year. In January 2022, the U.K.-based advocacy organization Global Witness said the facility was actually producing more CO2 than it was capturing in its early years. The project’s initial cost was a reported $1.35 billion, and the provincial government in Alberta contributed $745 million, while the Government of Canada added another $120 million.

The Alberta Carbon Trunk Line led by Enhance Energy captures carbon emissions from a fertilizer plant and refinery and sends them through a roughly 240-kilometre pipeline to depleted oil reservoirs at a place called Clive, aiding oil recovery. In March 2021, Enhance Energy issued a press release marking one million tonnes of CO2 sequestered.

As “green” projects, there are a lot of details to consider with CCUS proposals. Emissions during capture and transportation, for instance, wouldn’t help in reaching global climate goals. Similarly, anywhere where captured carbon is ultimately used to produce more oil and gas, which when processed, burned is likely to release more in greenhouse gases, isn’t necessarily a best option. Even pure storage plans need site-specific consideration and monitoring, for risk of gas leakage, to assure benefits claimed.

Last September, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) issued a report describing the 50-year history of CCUS, stating captured carbon has – to now – typically been used to help improve oil production. Projects have also been more likely to fail than not.

That said, detailing 13 projects worldwide, the organization also concluded: “Some applications of CCS in industries where emissions are hard to abate (such as cement) could be studied as an interim partial solution [for emissions] with careful consideration.”

And work pumping emissions from hard-to-abate industrial operations into closed aquifers offshore is a proposition all its own. It tends to be, amongst other things, more expensive than storage projects based onshore, according to officials. Even so, there are examples.

Some of the earliest work on offshore CCUS in Norway was spurred by that country’s 1991 carbon tax. The Sleipner Project in the North Sea came to fruition in 1996, the first large-scale CCS project in Europe. The IEEFA report found it to be “among the world’s most successful carbon capture projects.” It captured CO2 waste from production of natural gas at the Aleipner West field and reinjected it into the ground. Equinor and ExxonMobil were both major stakeholders (both active offshore Newfoundland and Labrador).

Norway gets a lot of attention from the offshore industry here for good reason. The country has naturally greater capabilities than the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. In R&D, in 2012 Norway opened the world’s largest test centre for work on CO2 capture and storage: the Technology Centre of Mongstad.

Anyone curious as to costs and challenges associated with offshore CO2 storage will be watching the country’s Landskip (in English “Longship”) project, led by state-owned Gassnova. The project includes planned carbon capture at industrial sites on land, like the Heidelberg Materials’s cement factory in Brevik on Norway’s South coast, creating liquid CO2 and bringing it to a Northern Lights receiving facilities in Øygarden, Norway, outside Bergen. From the port facility, the CO2 is sent by pipeline to an offshore reservoir, injected at a depth of 2,600 metres below the seabed. Working with Gassnova, Northern Lights is a three-way partnership of Equinor, Shell and Total.

The Northern Lights joint venture signed a shipbuilding contract in September for a third CO2 carrier, with two carriers already under construction. The vessels will be the world’s largest dedicated liquified CO2 carriers (the ships themselves run on LNG). Longship as a whole is expected to be one of the first projects to store “significant volumes” of CO2 gathered from across Europe, injecting it offshore. Of total costs of an estimated NOK 25.1 billion, 16.8 billion is expected to be contributed by the state.

For Atlantic Canadians trying to suss out what might be happening when, one thing to keep in mind is time. The Technology Centre of Mongstad is more than a decade old; the Northern lights concept report was filed in 2019 after a decade of government support for studies related to health and safety, economics and more. And even after any studies under the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador’s new program, there will still be issues to finish sorting through in legislation and regulation for any local offshore storage operations.

If anything, the new, starter R&D program in Newfoundland and Labrador is poised to help researchers already deep into oil and gas production-related science to become positioned to complete work highly relevant to evolving industry needs.

The lab and its researchers are already partnered with researchers from Dalhousie University and the University of New Brunswick on a proposal to Natural Resources Canada, seeking support for a project focused on CO2 storage potential in the region. The MUN research team is also working on a response to the CCUS Innovation Challenge. Among other things, James said the funds could allow for some upgrades at the lab to improve on existing capabilities and add to overall capability from a mechanical and equipment perspective in tests specific to carbon dioxide and carbon storage. The lab was first funded in 2013 by donations from the Hibernia Management and Development Company and the Research and Development Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador.

James said when talking about the potential for CCS locally, there are a lot of details for researchers to address on the technical side, well apart from political considerations or cost estimates. As an example, a major concern with any proposed CO2 storage project is leakage. It means there is need to establish for any given locations whether or not the particular pressure, temperature and chemistry of a site, a given reservoir, could risk leaks over time. Concentrated CO2, pressurized and compressed for injection into an old oil reservoir, will cause the saline water (think salty water) topping the reservoir to become more acidic, potentially eating away at the surrounding rock.

“We need to make sure how that water and CO2 is going to react together, as well as with the rock,” she explained. And then there are questions of capacity and long-term monitoring.

If there’s ever going to be any real confidence in answers given in response to questions around how much CO2, where it could be stored, how safe it would be, the confidence come in reducing uncertainties, she said. It comes with research.

Similar Articles:

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel