Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

Eighth in a nine-part series

In Atlantic Canada, would-be hydrogen producers are generally not talking about making liquid hydrogen for sale. For the ones who have advanced at all in planning and pre-engineering, they’ve been pitching hydrogen production for the purpose of producing ammonia.

But consider this: Atlantic Canada already produces a lot of hydrogen. It just happens to be made with natural gas and not with renewable energy sources. Irving Oil is a large producer, making 200 tonnes of hydrogen a day at its refinery in Saint John, N.B., the largest refinery in Canada. In turn, it uses the hydrogen to lower the sulphur content in a variety of refined products like diesel fuel. But hydrogen being used right now is made using natural gas. If sticking to the popular colour scheme, it would be considered “grey” and not “green” hydrogen.

Last summer, Irving Oil announced it was adding a 5-MW electrolyzer at the refinery, to produce more hydrogen but with fewer emissions. Atlantic Business Magazine confirmed the electrolyzer is scheduled to be fully operational next year. It will allow for production of up to two tonnes of hydrogen per day. The production will be powered by the local electricity grid (the detail is important since about 30% of total generation on the New Brunswick grid is still tied to fossil fuels and so, as in Nova Scotia, becomes a challenge).

Irving said the new electrolyzer will expand its hydrogen capacity, “with the goal of offering fueling infrastructure in Atlantic Canada.” There was reference in a press release to the new hydrogen being enough to fuel 60 buses, but the company hasn’t made any specific commitments on establishing and regularly supplying fueling stations. Irving’s decisions in the coming years, if it opts to push out into hydrogen retail (and no commitments have been made in that direction), would be a game changer for hydrogen locally. The Irving Group of Companies has a tremendous footprint in Canada and the U.S., with over 900 gas stations linked to it but also other properties and companies with experience in bulk distribution and technical servicing.

Theoretically, if this new hydrogen from Irving were used for the region’s first public “multi-energy stations,” provided for hydrogen vehicle fill-ups for light-duty cars and trucks, it will start to feed a need that doesn’t exist locally right now, with no existing fueling stations and no hydrogen vehicle retailers selling into the area. Irving would notably be supporting use in a new fuels market, not decarbonizing its existing processes at the refinery. At a macro scale, if companies encourage more use of hydrogen in this sense, growing global demand but not addressing emissions from existing hydrogen production and related processes, it’s not just possible but expected that at least some of the new market will be covered by more hydrogen made using natural gas. To keep that clean, oil refineries will need working carbon capture that comes with demands for billions in government subsidies and has so far not proven itself at scale, as Bloomberg recently reported in detail.

It’s important to note Irving’s idea with the electrolyzer is meaningful. The electrolyzer project was a first for a Canadian refiner and is a costly addition. Irving Oil president Ian Whitcomb has said it will accelerate the company’s understanding of hydrogen as a downstream product, “while creating a decarbonization pathway for our Saint John refinery.” But the company will not be racing in any particular direction yet. For that, much more infrastructure spending will be needed.

Decarbonizing the refinery might even compete with spending to capture opportunities beyond its footprint. Per a spokesperson, in response to questions on why the company is going with just one electrolyzer and if it plans for more: “We are actively pursuing renewable energy opportunities, including developing an integrated multi-year plan for generating value from the emerging hydrogen economy.”

In the very near-term, Irving will be making up to two tonnes a day of not-yet-green hydrogen, while up to 200 tonnes a day of hydrogen production at the refinery continues to be made with natural gas. It’s an example of the existing hydrogen challenge common to companies around the world.

Greening chemical plants

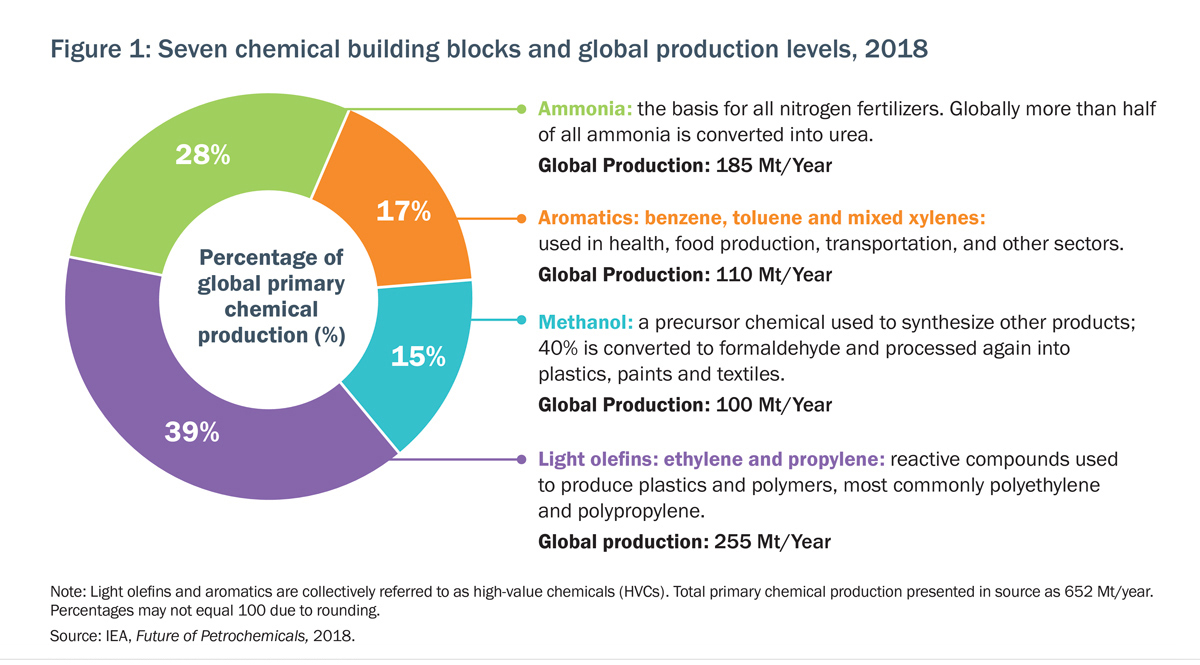

Sidestep to the even more complex but similarly challenged area of chemical production. Clean Energy Canada is a climate and clean energy program based at the Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue at Simon Fraser University. In March, program manager Ollie Sheldrick published a white paper on Decarbonizing the Canadian Chemical and Fertilizer Industry. He highlighted, as a division of heavy industry, the chemical and fertilizer sector—including production of everyday things like pharmaceuticals, plastics or ingredients for food products—was responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than steel and cement combined.

There are more than 3,300 chemical manufacturers in Canada. It’s a sector largely unfamiliar to Atlantic Canadians, though they will become far more familiar should new ammonia projects continue to be pressed for the region. For now, the country’s largest ammonia facilities are joined at the hip with our largest areas of natural gas production. That’s because natural gas is in the power mix but also is a feedstock, used in the production of chemical ingredients. Alberta is home to four of the top-five chemical facilities with the greatest greenhouse gas emissions and, Sheldrick noted, the 10 highest emitting sites produce more than half the sector’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

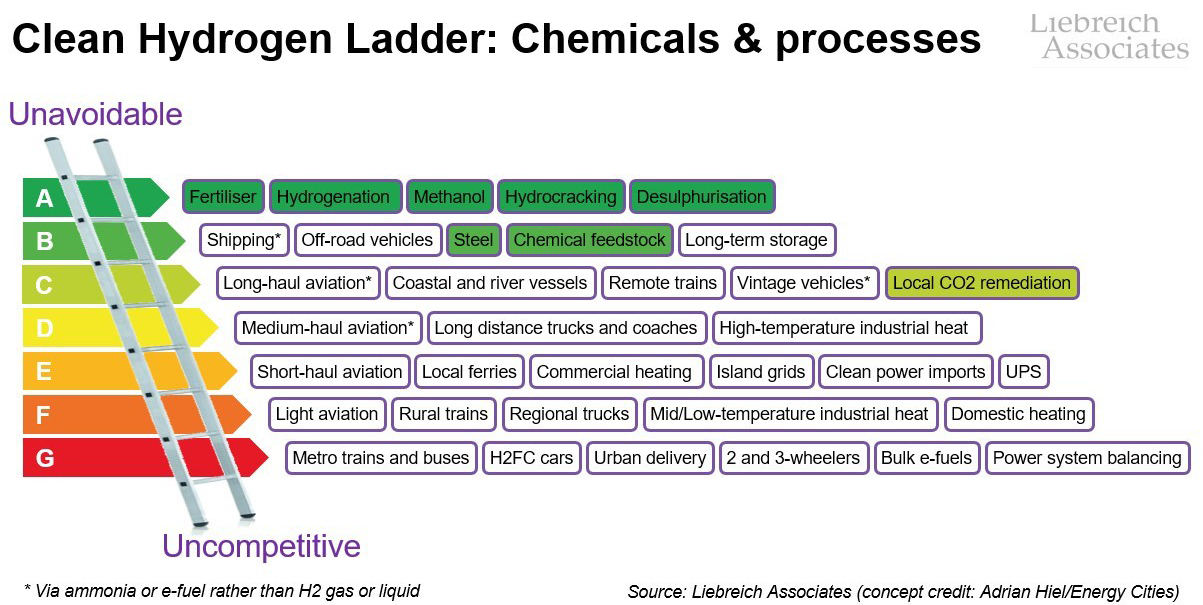

Refineries and natural gas facilities have generally been outfitted for the movement of a lot of natural gas, not hydrogen. There are operational parameters and safety regulations based on natural gas use. And there are huge costs in using less natural gas, capital and production costs that would raise the prices on goods for consumers. That said, maintaining the status quo isn’t an option.

One of Sheldrick’s recommendations, again just a few months ago, was for further research on the expected demand for electricity and clean hydrogen, and strategizing on decarbonization. There is work ongoing.

The chemicals industry will need reliable sources of hydrogen, he stated, “particularly clean hydrogen, which underpins the production of ammonia and methanol, as well as providing clean fuel to replace fossil fuel-based energy for heat in chemical production.”

While that may seem to point to a clear demand for even the largest green hydrogen build-outs proposed in Atlantic Canada, the chemicals sector needs carbon sources as well. It’s part of the reason for more talk locally of making ammonia and exports, versus hydrogen supply West.

Plants may look to use what is being called “bio gas,” or “renewable gas” (a greenwashing term), but have carbon capture and related add-ons. They can find ways to add green hydrogen, but are more likely there to self-produce or look for cheaper blue hydrogen (made with natural gas with carbon capture). If they go to green hydrogen, they will also need carbon dioxide, and that comes at a cost.

“In both cases (blue or green hydrogen), carbon is still required (carbon monoxide to create syngas for methanol and to convert ammonia to urea), but there is potential to reduce this carbon footprint by using a secondary source: captured carbon dioxide from another facility or activity.” And so these companies may try to capture carbon, from their own processes, or from other heavy industry.

Ammonia trade

In terms of demand for the production from chemical plants, as stated in the national strategy for hydrogen, the sector is mainly ammonia production, at 31 megatonnes of hydrogen per year (Mt H2/yr) and methanol at 12 Mt H2/yr. “Other minor applications, such as plastics, solvents, and explosives account for approximately 3 Mt H2/yr.”

Why so much for ammonia? “Ammonia is the main ingredient in nitrogen fertilizers such as urea and ammonium nitrate and is produced at large scale in Canada.”

Resetting even just fertilizer production, a large-scale industry in Canada, is costly work. One estimate suggests decarbonizing fertilizer production by replacing existing feedstock with green hydrogen could lead to a 55% increase in the cost of production. On the surface, it may seem like an issue for producers, but costs get passed on. Fertilizer is responsible for miracles in global food supply. The increase in the cost of fertilizer production could be partly swallowed by producers and offset, but the 55% estimate on cost of production further suggested it could lead to an increase to fertilizer costs for consumers of up to 25% and, in turn, higher per-tonne food costs by roughly 15%.

None of this is an argument against change. It’s about trying to understand where we are. It’s also about understanding what would-be green hydrogen producers in Atlantic Canada are looking for as their market. As part of how ammonia is produced today, using fossil fuels and particularly natural gas, the price of natural gas can directly drive up the cost of ammonia and more complex fertilizers. And where green hydrogen is not yet directly competitive with blue, this is what some of the would-be producers use to make their pitch to bulk traders.

An episode of the ARC Energy Ideas podcast, from the ARC Energy Research Institute, host and well-known Canadian energy analyst Peter Tertzakian was posing questions to Pattern Energy’s Canadian country head Frank Davis on planned ammonia production in Newfoundland and Labrador.

“Well certainly if you’re thinking about making ammonia as a hydrogen carrier, I would agree that today, right now where we sit, it’s a proposition that’s expensive, complicated and perhaps not as energy efficient as it will need to be in the long term. The way that we, and many other developers, are thinking about developing green ammonia projects is not necessarily to have this ammonia cracked open and reaccess the hydrogen on the receiving end. But it’s actually to service, right now, a robust and growing ammonia trade on the ammonia commodity itself,” he said.

Davis pointed to the price spike in natural gas and ammonia after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and said, for early moving projects like in Atlantic Canada, the company is focused on ammonia traders who are interested in hedging against future price spikes. In other words, while ammonia from Newfoundland and Labrador may be more costly right now, another spike in natural gas and ammonia could make today’s green ammonia and its suppliers the cheaper option, saving users money overall.

“We can essentially offer the market a long-term hedge against this gas variability,” he said, pitching it as an economic consideration for large traders of ammonia.

Tertzakian expressed skepticism on the plan. He pointed out that natural gas prices were relatively stable for years prior to the war in Ukraine. He also pointed to existing producers of ammonia internationally. Davis, in turn, said the company is responding to the expected growth in demand for ammonia.

Fertilizer lay of the land

Ammonia is a nitrogen fertilizer product. It can be converted to urea by reacting it with carbon dioxide. And that carbon dioxide is often sourced from the currently common steam reformation process for standard hydrogen production, where the production of hydrogen uses natural gas.

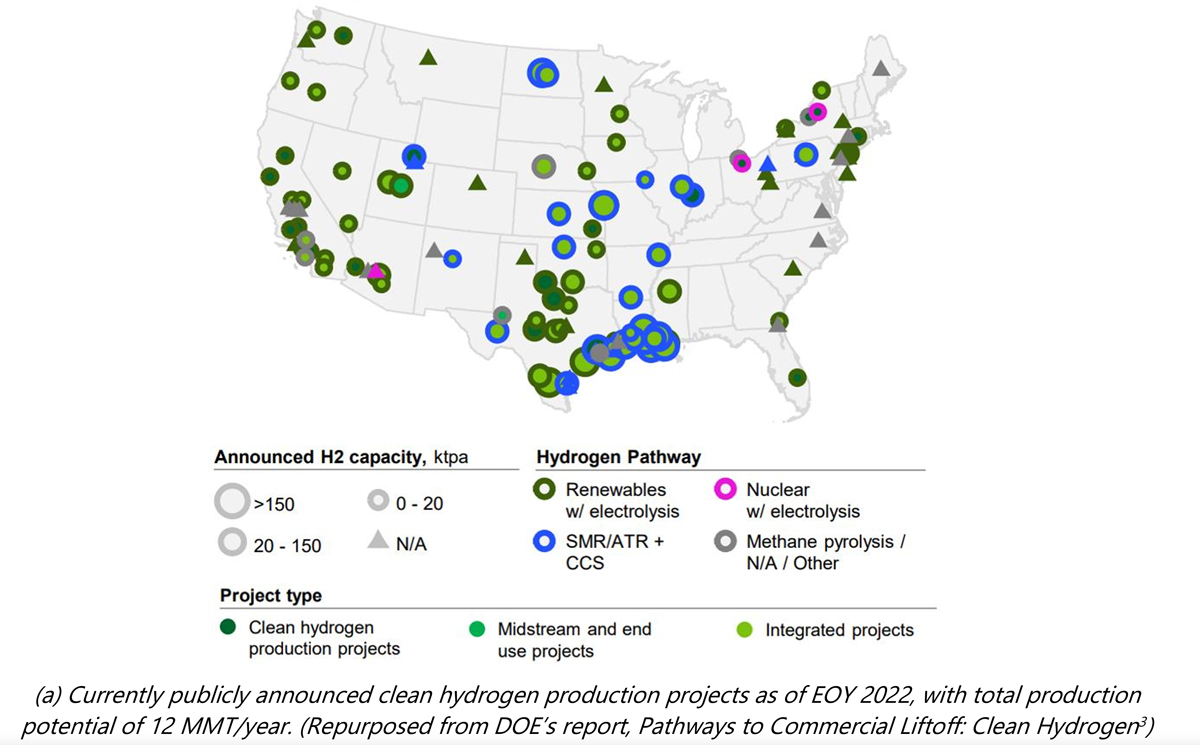

In evaluating hydrogen opportunities, the U.S. Department of Energy reported in March that about 70% of ammonia produced globally is for fertilizer use. And the U.S. doesn’t see a scramble for specifically green ammonia made with green hydrogen.

“It (ammonia) is a low-margin commodity that is unlikely to see high willingness to pay outside markets with strong carbon regulation (e.g. European Union). In the U.S., urea-based fertilizer would also require an alternative carbon dioxide source,” it stated.

It doesn’t mean the Americans aren’t seeing their own proposals for green hydrogen production, and then green ammonia production. For example, CF Industries, the world’s largest producer of ammonia, has teamed up with NextEra Energy Resources, the world’s largest generator of renewable energy, under a memorandum of understanding for a joint venture announced in April, proposing a green hydrogen development at an existing ammonia production facility in Oklahoma. It will include a 100-MW electrolysis plant, backed by a 450-MW renewable power facility, with the green hydrogen used to produce 100,000 tons a year of green ammonia.

Even so, “existing domestic ammonia capacity (for fertilizer) is expected to largely opt for reformation-based production pathways with carbon capture utilization,” the U.S. Energy report stated. That’s ammonia from hydrogen made from natural gas.

U.S. producers are looking to grow their ammonia production at the same time, to feed what they expect will be a larger global market for ammonia. They’re looking to feed into where ammonia made with natural gas and carbon capture is accepted, but natural gas resources are limited or maxed out. That includes Japan and South Korea, areas also eyed by local hopefuls.

Thinking beyond any competition from U.S. producers, it’s worth noting the U.S. is in turn concerned about competition from even lower cost producers in places like the Middle East and Africa.

Any producer in Atlantic Canada will also have to follow what’s happening further West in Canada where, as Fertilizer Canada has reported to the federal government, fertilizers are already big business and there is existing ammonia production. Canadian manufacturers produce about 12 million tonnes of nitrogen, phosphate and sulphur fertilizers each year (ammonia is included). Alberta sees $2.3 billion in direct economic benefit from fertilizer manufacturing, about $800 million to the GDP and almost 3,000 jobs, according to the association. Alberta has seven production facilities, one of the largest concentrations of nitrogen production facilities in North America, with more production within Canada in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario. The facilities produce ammonia (and upgrade products like urea and ammonia sulphate), and nitric acid (and upgrade products ammonium nitrate and urea ammonium nitrate). In a letter sent in March by association vice-president Cassandra Cotton to governments, specifically on the impact of the emerging hydrogen economy, Cotton highlighted expertise of existing producers in the safe production, handling and transport of ammonia and related products. The industry has detailed regulations, down to the number of ammonia-carrying cars allowed on a single train. The association rep stated the industry in Canada has been working to maintain operations with better prescribed standards, a.k.a. “industry-led codes of practice.”

“It is imperative that all new hydrogen and ammonia production facilities that are established to support the emerging hydrogen market and who are less experienced in shipping ammonia ascribe to similar high standard codes to continue to uphold safety when shipping ammonia,” it stated, in a consideration for any local environmental assessments.

It went on to highlight the investments of current producers into existing facilities and points out a standing issue is a need for Canada to assess how it can become a leader in low-carbon fuels for its own needs, and for exports, while maintaining domestic supply without driving up the price of that supply. It pointed out that over half of total nitrogen fertilizer applications in Canada involve urea and urea-based fertilizers, requiring hydrogen and ammonia but also carbon dioxide to produce. It noted no new nitrogen facility (for more advanced fertilizer products) has been established in Canada for over 30 years.

While Atlantic Canadian producers haven’t been asked publicly about the ammonia market in Canada, Fertilizer Canada has pointed to details in the Canadian market still need attention to avoid “price uncertainty” within the country as the energy transition presses on.

The nuances of electricity

Another important point and little discussed in Atlantic Canada to date, or particularly in Newfoundland and Labrador (elsewhere there has been excellent coverage, like that of the Halifax Examiner’s Joan Baxter), was the fact the green hydrogen projects are looking for support from the electricity grid. Davis said the plan for Pattern was to buffer ups and downs with some hydrogen storage, but the Argentia project and production by other producers will need to be fed electricity at times regardless. World Energy GH2 has been up front on a relationship with the grid, and in its environmental assessment filing has stated its planned “behind the meter” electricity storage. As others in Newfoundland and Labrador enter the assessment process, they will have to do the same, separately working through further details on interconnections with electricity regulators. But there is an expectation of tapping the grid at times, to varying degrees, while the argument is company wind farms will be able at times to, in turn, help grid managers and utilities cover their peak demands, feeding out stored electricity or feeding electricity while curtailing ammonia production.

Despite political talking points suggesting existing excess of electricity, the island of Newfoundland is not swimming in excess. The grid still relies on a fossil fuel power plant. Even with that plant, Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro forecasts a need for more bulk electricity production, just to meet community-based demands, like power for the electric vehicles set to come online in the coming years. It’s unclear how the needs of all of the proposed ammonia projects can or will be met, particularly in a way that does not chew into resources that would otherwise be used to meet local energy demands—including land for cheap wind power, for feeding power directly to the grid. Electricity is not yet possible to produce offshore, as permitting processes are still being put in place. But even when that happens, it has been more expensive to produce offshore than onshore.

Atlantic Business Magazine’s “Hydrogen Horizon” series is a high-level, moment-in-time look at the potential of hydrogen and its associated industry for Atlantic Canada. The level of demand for hydrogen production and the ability for Atlantic Canada to site competitive projects and service the markets, in a rapidly changing global energy sector, deserves serious and continuous evaluation.

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel