Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

Fifth in a nine-part series

“Bus” covers a lot. There are school buses, long-distance touring coaches and the public transit workhouses on daily routes. All are included in the very active conversation about “zero-emission” vehicles, where hydrogen is being considered an option. To date, hydrogen buses are far fewer in number than electric and hybrids. Experts familiar with bus fleets around Atlantic Canada say these vehicles will play a small role in local and regional bus services. Yet proponents argue they’re quick to refuel, and—at this point—they remain a possible source of future local, liquid hydrogen demand.

By 2030, the Government of Canada wants 30% of new medium and heavy-duty vehicle sales to be zero-emission vehicles (including smaller buses), ramping up to 100% by 2040. The federal government also wants 5,000 zero-emissions buses of all sizes on the road in Canada by 2025. As the national hydrogen strategy stated, “there is an initiative underway to encourage 1,000 of the 5,000 buses to be powered by hydrogen.” Realistically, as Atlantic Business Magazine was told, there won’t be 1,000 new hydrogen buses in just a couple of years. There’s also not likely to be 5,000 zero-emission buses total, even counting electric.

Currently, there are only about 300 zero-emission buses in Canada. If you add in promises by provincial governments and public transit agencies, when everything promised in recent months is delivered, you still only get to about the halfway mark on the total goal, as president and CEO of the Canadian Urban Transit Research & Innovation Consortium (CUTRIC), Josipa Petrunic, pointed out in a recent interview with Atlantic Business Magazine.

Petrunic expects many more commitments to zero-emission bus purchases will come in the next couple of years, particularly before 2026 and the end of the federal government’s current zero-emission transit funding program. And she expects there could be 5,000 zero emissions buses on the road by 2030, though mainly electric and hybrid models. Hydrogen buses are a different beast.

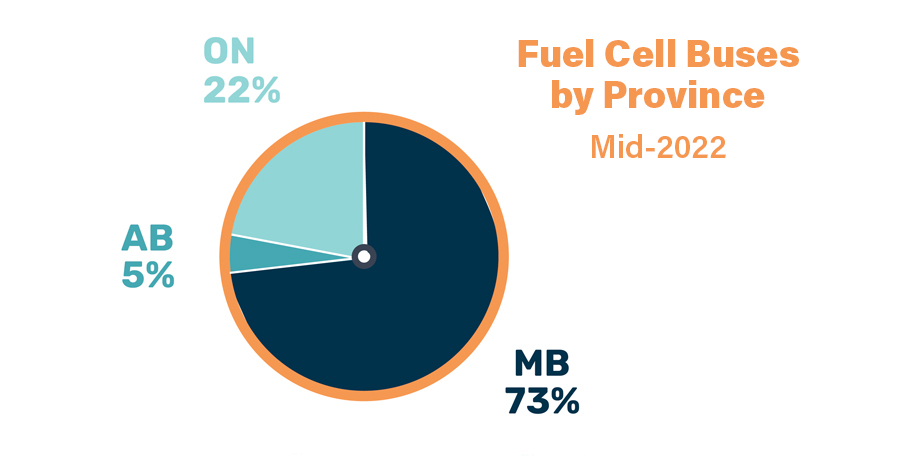

“Of those under 300 buses that are on the road, or very soon on the road across Canada, less than 10 are hydrogen fuel cell,” she said, adding she knew of only two hydrogen buses operating at the moment, in Edmonton. There are 30 to 40 more hydrogen buses promised, including for pilot programs in Winnipeg and more for Edmonton in the next couple of years. In some cases, fleet operators are still pinning down where their clean hydrogen supply will come from. Without a source of low-emission hydrogen, they will not help with goals for reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

Could go either way

Generally, buses relied on for everyday use demand a lot of energy. In Canadian cities, a transit bus may be based at a depot kilometres away from the point where they first pick up passengers. While in service, the machines are deadheading (running without passengers as they move from route to route, or off for servicing), carrying a lot of weight either with passengers or without, making constant stops and without much down time.

It’s unlikely entire city fleets will go to hydrogen, particularly when there’s access to electricity. Still, Petrunic expects fleets here and elsewhere in Canada may have at least some hydrogen in the mix, particularly after 2030. And she estimates 10 hydrogen-powered buses could need 300-400 kilograms of hydrogen a day, so a small fleet of 100 buses would demand 3,000 to 4,000 kilograms. That’s demand in Canada for liquid hydrogen. And for scale, a headline-grabbing hydrogen production project announced last year by Irving, to be located at its refinery at Saint John, N.B., would be enough to power maybe 60 transit buses—if the company wasn’t already planning on using the hydrogen in its own operations.

The biggest transit agency in Atlantic Canada operates in Halifax, with about 330 buses. Halifax Transit went to tender earlier this year for a feasibility study looking at the details of adding 40 to 60 hydrogen fuel cell buses to the municipal service. It already has some electric buses on order and, as CBC reported, is planning to get to at least 200 electric buses before 2030, but hasn’t decided what its whole fleet will look like by then. Hydrogen is being considered.

How many hydrogen buses will actually end up in this region? How much new hydrogen production will there be, and what part of the local market (if any firm, local market develops) will the local hydrogen producers be willing and able to serve? Of course, with hydrogen prices four to five times the price of diesel right now, it’s all really up in the air.

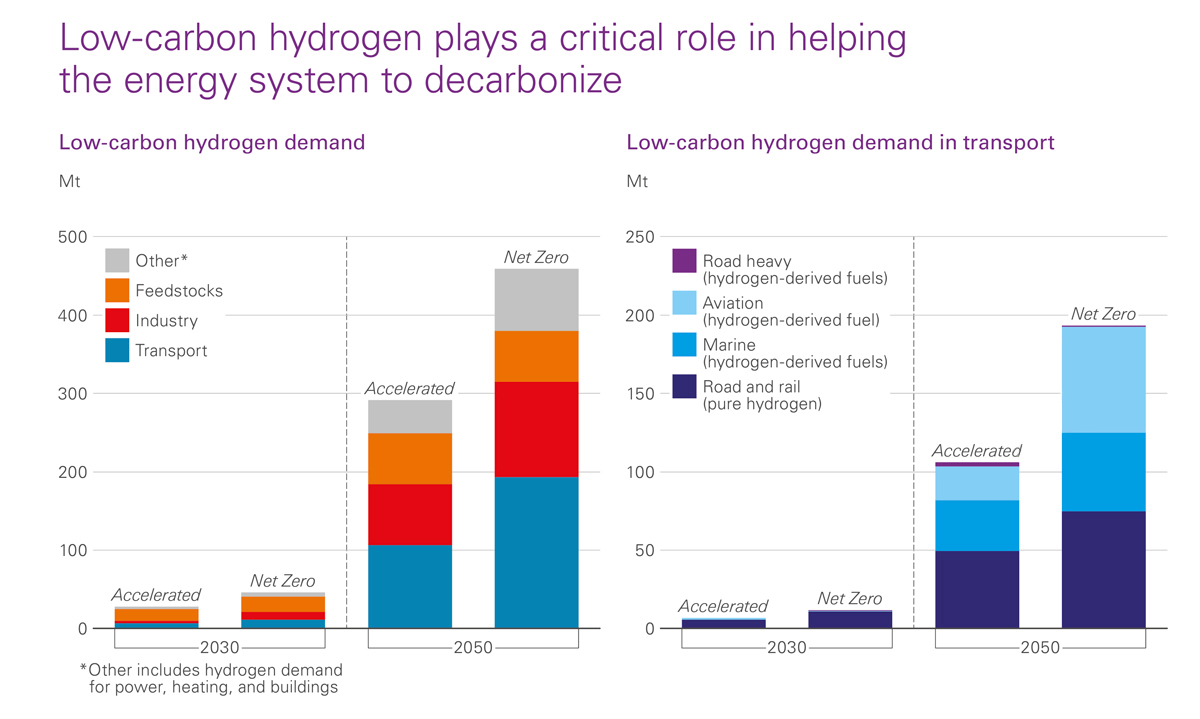

Hydrogen demand and supply is something people like Petrunic are watching closely and wondering about. Apart from buses, there are other areas—like trains or fertilizer manufacturing—where hydrogen is a proposed means of rapid decarbonization. Fundamentally, she said, there’s curiosity about all the talk of ammonia exports from Atlantic Canada, particularly locations closer to major centres.

“Why would we build an international supply chain for this stuff, to ship it to Europe, when we have demands and needs in Canada that are not being met? We have 15,000 buses, just the (public) transit industry, of which about 40% are probably going to have to be hydrogen,” she suggested, sticking to the electric-hydrogen split used by the federal government.

Leeway on the timeline for transition, improvements in tech, and really any number of things could affect that rough estimate, but if pushing for zero-emission bus services, hydrogen is in the mix and Canada is not ready. Getting ready would include building infrastructure to support bulk shipping within the country, and infrastructure at transit sites for fueling of buses in Canada. So far, Petrunic said, the limited funds from the federal government that are earmarked for public transit’s transition are flowing almost entirely into direct electric options, into electric buses. A basic supply chain for hydrogen that might feed even the largest potential users for long tour routes and in the better-serviced, big cities like Toronto and Montreal, doesn’t exist. And how can private businesses and transit agencies be motivated to propose related infrastructure, when there’s no certainty on hydrogen’s total infrastructure, cost and supply? Electricity is easier to try and gauge.

Hard realities of here and now

It starts with awareness. In reaching out to a few transport companies in Atlantic Canada, supposedly soon to be a globally renowned hub for green hydrogen production, one operations manager for a private company supplying coach services said they hadn’t even heard of hydrogen buses. In fairness, as with hydrogen fuel cell cars and trucks, the vehicles themselves are not even widely promoted here—a region with no hydrogen refueling stations right now.

In turn, hydrogen hasn’t been talked of much for transit. Moncton, N.B. is chipping in $30,000 on a $150,000 review for Codiac Transpo, planning for its transition. The Metrobus service in St. John’s, N.L., has announced it’s going ahead and paying $40,000 on the $200,000 bill for development of a detailed plan to electrify its fleet, with no mention of hydrogen.

The latter’s in line with British Columbia’s low carbon fleet program. That’s a vehicle replacement strategy for about 1,200 existing buses announced in 2019. It includes plans to expand the fleet, with an additional 350 buses, going all-electric by 2040. The federal government is helping with the cost of both the buses and charging infrastructure.

Earlier this month, Ontario premier Doug Ford was in Oshawa alongside Metrolinx transit officials, responsible for public bus services in Southern Ontario, to show off a pair of new electric buses. These GO buses have been tested without passengers for more than a year. They run about 225 kilometres in winter, longer in summer, before needing a charge that takes between three and four hours. Their continued testing, now with passengers, will help shape Ontario’s approach to zero-emission vehicles, but will also likely influence many others. The electric buses are about $1.5 million a pop, costing more than twice the traditional $700,000 fossil fuel model, but are electric and not hydrogen.

Changing what can be changed using existing electric, Petrunic said there’s a risk support for the transition will wane before the hardest-to-decarbonate routes and charters are completely addressed. And more broadly, there’s a risk government funding for the transition is being gobbled up by private companies in larger sectors including refiners, chemical manufacturers, who are facing a need to transition to lower-emission operations and are simply moving faster.

Improving, to an extent, on costs

Transit companies are not at square one, as some progress has been made in settling what technically and financially are the best options. Hydrogen buses have seen past demonstration projects funded by the federal government. There were projects in the 2000s involving Ford and Air Liquide, a company making hydrogen in Quebec, including one in Ottawa in 2007-2008, with a bus running on Parliament Hill. Another demonstration project was on Prince Edward Island, where two hydrogen fuel cell shuttle buses (picture shorter than a city bus or school bus) were introduced by Charlottetown Transit (a.k.a. T3 Transit). These Island buses were run until federal support ran out in 2010. Among other things, both projects were said to have provided a chance for transit authorities to get more familiar with the related infrastructure and operational demands.

And what was once the world’s largest fleet of hydrogen-powered buses came into service in Canada for the 2010 Winter Olympics. There were 20 buses assigned to serve Whistler, as a demonstration project that continued for five years, to 2014. People were aghast at the cost then, projected to be about $90 million all-in for the buses, related infrastructure and operating expenses. The provincial and federal governments covered the cost at a roughly 50-50 split. But the focal point was the buses, estimated at an average $2.1 million, or between three and four times a diesel-powered alternative. The buses were also more costly to maintain than alternatives. The kicker for criticism of the testing was the “green” factor, as the David Suzuki Foundation pointed out the green hydrogen being used for the buses was being trucked in from an Air Liquide’s production facility across the country in Becancour, Quebec. At the end of five years, with other lessons learned, the Olympic buses were sold back to supplier New Flyer Industries for $1 million, as part of a purchase contract for buses running on compressed natural gas (CNG). BC Transit confirmed the contract was signed in the fall of 2015 and the last hydrogen bus left Whistler in April 2016. For its part, manufacturer New Flyer found the project achieved its objectives in terms of operational testing. On the technical side, it successfully informed the next generation of fuel cell designs, leading to the company’s more advanced Xcelsior CHARGE H2 and Xcelsior CHARGE FC models.

The manufacturer also sells trolley electric buses (with the overhead electrical connection), natural gas buses and hybrid buses. On the idea of battery electric versus hydrogen, a spokesperson told Atlantic Business Magazine the company believes both are going to remain in play, with public transit agencies and private transit companies mixing their fleets to meet their needs, based on the specifics of their services and factors like available infrastructure and terrain. But, like Petrunic pointed out, costly infrastructure and unreliable supply of hydrogen remain hurdles — if you want hydrogen.

“Oftentimes the challenge of implementing a hydrogen fuel cell fleet include the availability of hydrogen; the cost of building hydrogen infrastructure; and sourcing of ‘clean’ hydrogen that has a higher environmental rating. In general, we see more battery electric purchases because the infrastructure is more readily available in North America, and therefore it is an easier implementation,” they said, in an emailed response to questions. However, there is continued interest in hydrogen fuel cell buses based on their offered range, weight and faster fueling times.

N.L.’s challenge vs. rest of Atlantic Canada

In talking costs and availability of public transit, Newfoundland and Labrador has an existing problem, potentially made worse in the transition. The small population density in communities, and overall size of geographic area for transit to cover, has always been a challenge. Now, there are the costs to slashing emissions and a call for more public transit, when existing services are already struggling. It makes the question of electric, hydrogen or other feel far down the list of concerns.

Jason Roberts is the owner and general manager of DRL, the only bus company running daily service across the island of Newfoundland, also offering charter services. He says he’d make use of zero-emission buses today if they logistically and financially made sense. As it stands, they don’t and he’s “very doubtful” he’ll see them in Newfoundland and Labrador in his lifetime.

Roberts said he’s interested and has been looking at electric buses for possible use in shorter-haul charter services. But there are challenges beyond just having buses available.

“It’s support for us too,” he said, explaining he is already challenged to find anyone anywhere on the island willing to service, and capable of servicing, one of his newer diesel motor coaches.

A bus may be on the side of the highway and in need of service 400 km away from where the mechanic is based (imagine running Moncton to Fredericton and back twice over), and not every mechanic on the island can service the machine. In fact, few can. He’s found himself high and dry, looking to Nova Scotia for someone he can fly in. He shudders to think what hydrogen buses would mean, in terms of ready and available service. He suggested it’s likely suppliers will offer to service vehicles in their marketing, but see rural Newfoundland or Labrador as too remote and costly a spot to base personnel.

Costs of the buses are no small thing. They also are, as Roberts points out, linked with basic logistics. Logistically, for example, electric buses could work for shorter charter runs but wouldn’t get him the 900 kilometres from St. John’s to Port aux Basques. Looking at the distance, Roberts said the option would be to have more buses than he has right now to cover the same run, with some at stops along the way, having passengers switch from a largely depleted to a charged bus. He also sees trouble in, for the models he has seen, lack of cargo space. Hydrogen might arguably work better on distance but still be a problem on other fronts, including the issue of cargo, plus the added issue of available fueling stations that aren’t at risk of disappearing.

Roberts pulls back from going too far on any of it. Mainly, because he’s already losing money on the cross-island service, struggling financially, and in no place to pay even a share of costs on a new fleet of buses, whatever the type. Roberts said he talked with the provincial government during the height of the pandemic about subsidies but swears he’s yet to receive any money. His revenues are coming up since those recent lows, but with fuel prices up, fuel ended up costing him an extra $600,000 last year.

“Maybe they want it to go. I don’t know,” Roberts said of his cross-island service.

If he shuts down, any regular bus service disappears altogether for the bulk of the province. Beyond St. John’s, a few, and only a few, tendered services in larger communities like Corner Brook would remain, along with event and tourism-based charter services you could count on one hand. Governments at all levels talk a lot about public transit, but focus on Canada’s largest cities, adding or extending where a service already exists.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the “roads for rail” program marked the end of train service on the island portion of the province. Bus services were brought in. Those services fell away bit by bit over time. Of course, that was before the government was applying a growing carbon tax to fossil fuels.

After taking a close look at Canada’s new Clean Fuel Regulations, targeting reduction of the carbon content of gasoline and diesel, the Parliamentary Budget Office has found the policy will be felt more by lower income households by 2030. It comes in addition to the federal carbon tax. And it’s also expected to cost Saskatchewan, Alberta and Newfoundland and Labrador more, given fossil fuel dependence in these provinces, making additions and not just transitions for public transit an even tougher sell, given existing costs.

Atlantic Business Magazine’s “Hydrogen Horizon” series is a high-level, moment-in-time look at the potential of hydrogen and its associated industry for Atlantic Canada. The level of demand for hydrogen production and the ability for Atlantic Canada to site competitive projects and service the markets, in a rapidly changing global energy sector, deserves serious and continuous evaluation.

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel