Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

Seventh in a nine-part series

For land, sea, and air, companies have been, more fervently in the last several years, pitching hydrogen as a means to power transportation. The issue is not “if” hydrogen can be used for trains, boats and planes. It’s when emerging options might start to be manufactured in greater number, marketed to end users writ large, and more importantly to what degree these hydrogen-based options will compete with electric, natural gas and hybrid options. There is also the possibility of a delay in moving large transport vehicles off of fossil fuels, despite all regional public policy signals and clear global climate change goals.

Whatever happens, the promotion from manufacturers and would-be manufacturers of all zero-emission vehicle options is already coming fast and furious. This will continue, with the new rush of R&D spending and government manufacturing incentives relating to hydrogen.

As an anchor, when hearing about or reading about new trains, boats and planes, in considering the extent of hydrogen’s reach, it’s worth taking a moment to recall some of the reasons why hydrogen isn’t already in wider use as a fuel. Hydrogen is very light and carries more energy per kilogram than our standard fuels. However, it’s terrible on volume. It doesn’t like to be compressed. You can liquify hydrogen, but it is an energy intensive process. It takes far more energy to liquify hydrogen (requiring a colder temperature) than natural gas, and more energy to keep it liquified on any journey. As it stands, you will need to make more trips to move the same amount of energy or have a larger container versus liquified natural gas (LNG). And a larger container is a problem on a ship or oil platform, or wherever space is at a premium. Plus, there is a fair amount of natural gas infrastructure in the world. There is plenty for kerosene, even more for diesel. Where hydrogen is described as cost-competitive with fossil fuels, the costs tend to be a comparison on production costs, and not include the very clear gap in infrastructure when it comes to bulk transportation and distribution (people don’t think about gas stations when it comes to heavy transport, but the equivalent of gas stations and containment would be part of it, bulk delivery to those stations another). That’s not a suggestion from Atlantic Business Magazine for rapid construction start on all fronts, just a factual observation the gap exists.

Fuels have to be moved around. They have to be shipped and trucked to fueling stations, moved point to point at ports, refineries and other industrial sites. Hydrogen is an energy product that can be made at the end of an electrical wire and allow the renewable energy to be moved around the world. That doesn’t mean it’s the most efficient means of providing energy at all points right now. And costs of production can be higher than the lows, depending on the region and what’s available.

Is hydrogen really being adopted for trains, ships, planes, growing the hydrogen demand? How likely is it hydrogen will be adopted for machines operating in Atlantic Canada, potentially contributing to a local market a hydrogen producer might feed? At this point, there is little and arguably nothing to suggest hydrogen options are taking over locally. The future is undecided in terms of the degree it might capture the local market, and at what speed. As for feeding export markets, it will be a matter of how quickly any demand emerges and competition within and without Canada for servicing any new demand, including from existing hydrogen producers.

Trains

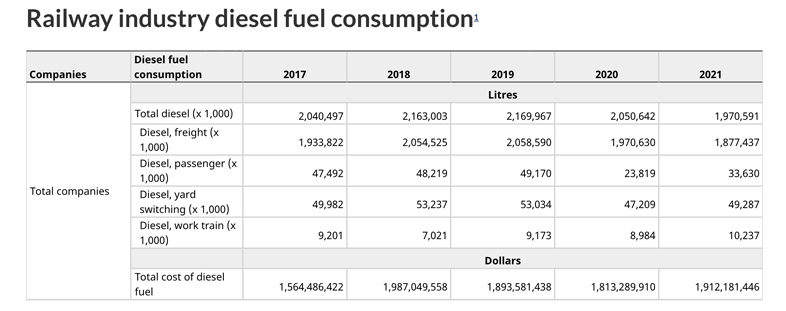

Like cars and trucks, trains come in many different shapes and sizes, with varying purposes and differing energy demands. The main split is into passenger and freight operations. Freight operations represent about 95% of fuel consumption and total GHG emissions from rail in Canada, burning through 2.1 billion litres of fuel each year. About 87% of these freight services are mainline operations, mainlines being as they sound: running more locomotives, and with trains traveling longer distances when all of the travel in a year is totalled up.

Per the Railway Association of Canada, in 2020 there were 3,756 locomotives running freight service in Canada, with over 2,900 on a main line. All told, these trains account for about 94% of the fleet. Passenger trains landed at a count of 239 locomotives, or about 6% of the Canadian fleet. And, in comparison to freight, passenger trains burn less than 5% of total fuel.

Canada’s main rail companies are Via Rail, Canadian National Railways (CN) and Canadian Pacific Railways (CP). The operations reach into Atlantic Canada but the bulk of use is elsewhere and, as a study on Maritimes hydrogen demand stated, “demand from this sector (in the Maritimes) will be dependent on their larger national strategies.” The industry does have a roadmap to decarbonize.

Are they looking at hydrogen? The short answer is yes, but right now there are limits.

“Hydrogen is a promising potential solution to further reduce emissions (…) Hydrogen is one of several options being actively explored and tested by Canadian railways,” stated Railways Association of Canada manager of policy, environment and programs Ben Chursinoff, in an emailed response to questions.

“Given Canada’s terrain and climate, extensive testing is always required to understand and work through technical, operational, economic and safety considerations. This will advance not only hydrogen technology but also increase demand for hydrogen and support domestic production,” he stated.

Basically, everyone’s working on settling on best solutions. Indications are commercial operators here and around the world are likely to ultimately head down a path similar to trucking—leaning into electric wherever electric works, while looking at hydrogen as a possibility for geographic areas that prove difficult to electrify, including long-haul freight operations. Any determinations in the next few years will come with the caveat that these are decisions based on what is available right now that makes sense for businesses. Longer-term outlooks, like anything suggesting hydrogen uptake at 2050 or beyond, should be taken with a pound of salt.

The bottom line is it’s unclear how much hydrogen trains in North America might demand and when. And despite being ahead in the introduction of hydrogen trains, it’s a similar story in Europe.

A 2019 report from consultants with Roland Berger, for the European Union’s Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking (now the EU Clean Hydrogen Partnership) and the EU Shift2Rail initiative, cited market studies and industry interviews when stating, “there are no show-stoppers for the use of hydrogen technology.” In translation: hydrogen isn’t the cut and dry answer for trains. The consultants said costs for related infrastructure needed to continue to come down. It also flagged existence of country-specific regulatory hurdles that could delay rapid growth of hydrogen use. They found fuel cell hydrogen trains could be cost-competitive with traditional diesel in a lot of cases, but diesel isn’t the only option. Including case studies in cooler areas of Sweden and Estonia, the report suggested hydrogen made the most sense on non-electrified routes over 100 kilometres, or in areas with low use, up to 10 trains a day.

Hydrogen fuel cell-battery hybrid trains, often referred to as “hydrail,” are in service, but generally speaking hydrogen is battling against direct electric options, with shares of the future market unsettled. But as stated in the European Commission’s report “Electrification of the Transport System,” 60% of the European rail network is already electrified and 80% of traffic runs on these electrified lines. And given that report was produced in 2017, the figure is now likely higher. On owner costs, electric batteries are cheaper to date than hydrogen made from fossil fuels, and that hydrogen is cheaper than anything run on hydrogen made from renewable power, like the kind proposed in Atlantic Canada. Europe favours “green”, but the price difference is still material. It should also be said there is opportunity for train operators in Europe to self-produce hydrogen or contract production in Europe, or they might look to suppliers importing from countries other than Canada.

In North America, the topography, the population density and service demands for trains are different, and operators are now testing their options. Hydrogen is in the mix. Starting with passenger trains, hydrail is now being given trial runs. Alstom is doing a pilot with its Coradia iLint hydrail passenger train in Quebec this summer, with the private operator of the Charlevoix railway. The pilot is using green hydrogen made in Quebec by Harnois Énergies. Vancouver-based HTEC is supplying the refueling infrastructure.

HTEC is the company that in 2022 acquired the consulting firm that acted as lead author on Canada’s national hydrogen plan. The consultant, Zen Clean Energy Solutions, also produced both the feasibility studies for hydrogen for the Maritimes and Newfoundland and Labrador (completed in 2020 and 2021 respectively), referenced often in local debates.

Hydrogen supplier Harnois Énergies may become more familiar in Atlantic Canada in the coming years, as that company is currently awaiting Competition Board approval for purchase of a portion of the retail gas stations and convenience stores of the “Wilsons Systems” brands, being Esso Go Stores and Wilson’s Gas Stops. The operations are being purchased from Ailmentation Couche-Tard. That company was required to sell some of the network of gas stations, as a condition of the approval of a takeover of the Wilsons Systems business in August 2022. Harnois’ position in taking on the stations is of note, given Harnois was behind the first “multi-energy station” (the corner gas station also offering hydrogen fuel in Quebec City), showing an interest broadly in hydrogen end uses and related services.

The Alstom passenger train demonstration project is estimated to cost about $8 million, with the province of Quebec kicking in $3 million. The train will run on the Réseau Charlevoix rail network, along the St. Lawrence River, between a station in Quebec City and one in Baie-Saint-Paul. The regional county including Baie-Saint-Paul has a population of less than 13,000, introducing one of the real challenges in Canada for hydrail. Namely, plenty of rural areas not unlike Baie-Saint-Paul, or even more populated, searching right now for money for the expansion of rail service or (more commonly) introduction of any public transportation. Governments and operators are challenged by the demands on limited public dollars.

Regardless, the expectation is there will be at least a few lessons on hydrogen out of this Quebec trial for federal officials, Canadian provinces and U.S. state leaders. The Coradia iLint model is already well-traveled, with Alstom reporting more than 220,000 kilometres of service in eight European countries as of earlier this year. The train is designed for lines that are not already electrified.

In Canada, hydrail has also been a focus at the University of British Columbia, at the SMARTer Growth Research Lab under engineer Dr. Gordon Lovegrove. Lovegrove and his team have worked with the National Research Council and Transport Canada on a research project started in 2022, including work with full-scale prototype, to help identify any gaps in operational knowledge and national regulation, for starters. Lovegrove’s team has also worked with the Penticton Indian Band and regional entities on detailed concepts for hydrail developments in the Okanagan Valley (known as the Okanagan Valley Electric Regional Passenger Rail or OVER PR project), and Fraser Valley. Running contrary to the beliefs and requests of local mayors, the researchers have said it is less costly to add hydrail, than expand existing highways.

Another prominent passenger rail service proposal involving hydrogen is in Alberta, where hydrail has been proposed by Liricon Capital for a new link between Calgary and Banff. The rail line would be part of the Banff Eco-Transit Hub, in a proposed redevelopment of Banff Railway Lands. The company has suggested the project will be completed in 2025 and has an estimated cost of $1.5 billion, but it’s still relatively early in the development process. A draft of the redevelopment plan has just been released, and the provincial government kicked in $5 million to support advancement of the project.

Developments in Western Canada will likely be served by new hydrogen production being planned in that region, where provincial governments have also been aggressive in financing hydrogen-related infrastructure and pilot projects.

As for the operator plans, Canadian Pacific (CP) moves the equivalent of 52,000 carloads of customer goods and materials each week in Canada, according to a company report on operations, and diesel rules the day for now. Reading through multiple reports in the fine print, the company used 995 million litres of “locomotive” diesel in 2018, with associated greenhouse gas emissions for its total inventory of more than 3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide and equivalents. The writing is on the wall for changes, given the $50 per metric ton of carbon tax in Canada that’s expected to increase to $170 by 2030. The company has modelled the financials, suggesting “a potential impact of up to $331 million by 2040.”

CP has established a Carbon Reduction Task Force. The company has also been up front in saying, out to at least 2030, staff will be “evaluating alternative propulsion technologies – particularly hydrogen-based solutions – that are necessary to longer-term reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from the freight rail industry.” The evaluation work includes an ongoing program in Western Canada involving the conversion of three different types of diesel-electric locomotives to run on hydrogen fuel cells and batteries. The project is backed by a $15-million grant from Emissions Reduction Alberta. It includes the addition of both hydrogen production and fueling facilities at CP rail yards in Edmonton and Calgary. The hydrogen is being made using solar power from a 5-MW solar farm built for about $10 million at CP headquarters in Calgary, with an electrolysis plant with 1-MW electrolyzer. At the other end, in Edmonton, there is a small-scale steam methane reformation system, using natural gas to make hydrogen there. The project will run to at least 2025.

CP is excited to share video of its fully painted hydrogen locomotive – which has run under its own power! The project team is now preparing for field-testing with the H2OEL. This is a significant milestone for CP’s Hydrogen Locomotive Program. #SustainablyDriven pic.twitter.com/M5njG3nJOZ

— CPKC (@CPKCrail) January 24, 2022

Canadian National (CN) trains move more than 300 million tons of goods around North America and claims the title of most fuel-efficient railway on the continent. Still, as a rep told CBC last year, 85% of the company’s emissions come from diesel-powered locomotives. For CN, testing around zero and low-emissions trains is starting on electrification and batteries. A subsidiary announced purchase of a battery-electric locomotive from Wabtec in 2021, for trials in Pennsylvania. The train is expected to be online later this year.

H2 V Énergies Inc. is a biofuels start-up promoting green “bio-hydrogen,” “bio-ammonia” and “green methanol” production in Bécancour, Que. In 2021, president and CEO Normand Goyette suggested, in a presentation to members of the Canadian Senate, just what it would take to switch all CN and CP locomotives to green hydrogen. Goyette stated annual demand from the two could total about 656,000 tonnes (723,000 tons) of hydrogen. The demand for CN alone, at 460,000 tons, would be roughly ten times H2 V Énergies’ production at Bécancour. It would be about twice what World Energy GH2 could produce, if all proposed phases of its project were built. But that’s a hypothetical demand and could include hydrogen used to, in turn, produce fuels other than ammonia, a step would-be local producers have not pitched.

Ships

There is no ship in Canada approved to operate with a hydrogen-based power system. It’s a standing question as to how fast and to what extent that might change.

Models do exist around the world. There are explicit Canadian technical standards and place-specific infrastructure demands to meet here, for a start. But as people responsible for different types of boats in the region have told Atlantic Business Magazine, the timing and extent of any uptake of hydrogen or electrification is not at all clear. If not considered relevant to investment decisions on any proposed, local hydrogen production, given the focus on exports, the timelines are still relevant for any discussion of when local people might get to sail on low-emissions machines and local hydrogen demand that would then have to be met.

Hydrogen proponents suggested Transport Canada could nudge hydrogen options forward in the procurement for the scheduled replacement of the ferry MV Holiday Island, once operating between P.E.I. and Nova Scotia. The ferry’s planned timeline for replacement was affected when it was damaged by fire in 2022. It’s set to be scrapped. A representative for Transport Canada told Atlantic Business Magazine the replacement vessel will be powered by a diesel-electric propulsion system with batteries for energy storage. “The new vessel is also being designed with space reservations that could accommodate additional batteries or hydrogen fuel cells,” they said, with no commitments on the fuel cells.

Transport Canada also has a Clean Marine Research program with multiple projects ongoing. There is a project looking at electric “landing craft”; an electric fishing vessel pilot with a nine-metre vessel with Nova Scotia’s Glas Ocean Electric; an electric tug with B.C.’s Seaforth Environmental Services and, in hydrogen, a safety assessment looking at hydrogen bunkering and fueling systems for harbour cruise boats. There are research buckets, and Transport Canada is also involved with a project looking at development of a battery-electric tug operating from shore power systems and “renewable diesel” use in tugboats.

In Atlantic Canada, the ferries of Marine Atlantic are some of the most recognizable vessels in the region, in their regular runs between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador. To date, Marine Atlantic has made no explicit commitments to switching to vessels running on liquid hydrogen, ammonia or hydrogen derivatives like methanol, no matter the timeframe. The company has not made any commitments to use hydrogen or other “green fuel” from a local supplier. The Crown corporation’s next ferry will start operation in 2024, newly built and under lease from Stena North Sea Limited. It won’t use hydrogen. It runs on a mixture of liquid natural gas, diesel and lithium batteries.

“With our new charter vessel, we have moved in the direction of LNG for future use when a local source exists. As well, we will utilize battery banks for thruster propulsion in and out of our ports,” said Marine Atlantic spokesman Darrell Mercer, in an email. He didn’t go so far as to say the door is shut on hydrogen, but it’s a far cry from any suggestion of local hydrogen demand being just around the corner.

“Other fuel sources such as methanol may be a future option on our existing fleet; however, sources such as ammonia and hydrogen will most likely require added infrastructure while could take away much needed deck space. These options could be part of future fleet replacement considerations should there be a local continuous fuel supply and infrastructure supports in place in the future,” he stated.

Methanol is an important mention. Green methanol can be produced using hydrogen made from renewables, but the process also requires another ingredient, for required carbon content. Commonly, the carbon comes through use of biomass or capture of emissions from a cement, silicon or chemical processing plant, as examples. And just to be clear, Marine Atlantic has never suggested any methanol it uses would or should be locally made.

Moving beyond the largest ferries, owners of smaller provincial and privately-operated ferries have not yet indicated plans for the transformation of their fleets. Eyes are on international pilot projects. Of note, there are few routes around Atlantic Canada where passenger ferries would need to carry more than 300 people and 80 standard vehicles or equivalent in a run. Norwegian operator Norled is now running a liquid hydrogen-powered ferry capable of making those runs, called the MF Hydra. Another, smaller hydrogen-powered ferry — using hydrogen made from fossil fuels — is starting testing in San Francisco Bay, U.S.A. Meanwhile, the 80-person Hydro Bingo was reportedly the world’s first passenger ship with hydrogen-diesel engines and tested last year with a bop around Tokyo Bay in Japan. These are all representative of a still emerging product that will have to compete against existing and emerging battery-electric options.

In Norway, Norled’s MF Hydra made its first sailing at the end of March. “There are only two parties in the world that use liquid hydrogen as a fuel. These are Norled, with the MF Hydra, and then the space industry using it as fuel for launches. This says something about the giant technology leap now taken for the maritime industry,” said Norled’s chief technology officer Erlend Hovland.

Norled also launched the first battery-operated, propeller-driven ferry, the MF Ampere, the better part of a decade ago, and there are dozens of electric ferries now in operation in Norway. That includes the first all-electric fast ferry, launched in the fall of 2022. All-electric ferries do come large enough to do the local work. The Basto Electric can carry 600 passengers and 200 cars or similar light-duty vehicles. That’s compared to the 240 passenger, 36-vehicle capacity of the MV Flanders or the 200-passenger, 64-vehicle capacity of the MV Legionnaire in Newfoundland and Labrador.

There are electric hybrid ferries in use in British Columbia. There are half a dozen 300-person, just under 50-car-capacity electric ferries and there has been some consideration of electrifying the SeaBus fleet serving Vancouver harbour crossings. Greenline Ferries has proposed introducing an electric catamaran to connect Vancouver with destinations North.

The fight for hydrogen involves arguments related to longer sea crossings, and service arguments like charging times versus fueling times. Mainly, there are the cost calculations, where electric is winning out on many fronts. At all levels, in capital costs, in supply requirements, the MF Hydra is reported to be costing Norled more than the MF Ampere. That said, it was pursued to fill a specific gap that still exists, for servicing longer routes.

Moving to any form of zero emissions at sea comes with a hefty initial price tag, as Nova Scotians discovered in considering a fully electric Bedford (Mill Cove) to downtown Halifax ferry service. Among other things, given charge times, the city was told fully electric would require more vessels, and ultimately the cost over a traditional diesel service amounted to an extra $35 million.

Apart from ferries, cargo vessels are essential for the islands of Atlantic Canada, with some larger, private service providers. In August 2022, Newfoundland and Labrador-based daily outlets reported Oceanex and Flensburger Schiffbau-Gesellschaft (FSG) have a memorandum of understanding to work together on designing a new container vessel, with emissions top of mind. “The companies plan to investigate the use of alternative fuels like ammonia, methanol, synthetic and biofuels, as well as hydrogen for the Oceanex fleet of vessels,” stated a report from Saltwire on the partnership, but the exact details on what might come aren’t yet clear.

The fishing industry is another area to consider, with a very different dynamic given the financial pressures on individual enterprise owners, particularly with smaller boats. Competition with electric is also more aggressive with smaller boats. Oceans North and the Membertou First Nation are currently looking at possible electrification, for development of a zero-emission lobster fishing fleet in the region. In P.E.I., Aspin Kemp & Associates (AKA) has showcased a hybrid fishing vessel. Atlantic Business Magazine reached out to the Prince Edward Island Fishermen’s Association (PEIFA) for an update on its pilot project to test electric, hybrid and other fuel propulsion systems that are alternatives to all diesel on nine inshore lobster fishing vessels. That project has support from the Atlantic Fisheries Fund but was delayed after responses to an initial request for proposals. Senior advisor Ian MacPherson said all of the proposals offered diesel-electric hybrid systems. The hang-up was on costs. However, some design edits, advancements and further work with interested manufacturers has given the project new hope, and the PEIFA is heading out with a fresh RFP. MacPherson said it is still open to proposals for hydrogen options. He added fish harvesters are interested in emerging options for their boats, and there will be options better suited to different types fishing and fishing areas, but cost is a natural barrier to adoption. That’s particularly true in an industry being challenged by “big picture stuff,” from higher fuel costs, insurance costs, even where catch rates drop on a particular species. Enterprise holders won’t take on new technology they can’t pay for, even if they’re convinced on things like reliability.

“Ultimately it comes down to what are the economics on it?,” MacPherson said.

Overall, diesel-electric systems are still more commonly pitched as a next-step for boat owners.

Canada’s offshore oil fields are served by a trio of shuttle tankers. The tankers have diesel engines, and they burn bunker fuel to keep heat to the crude oil as it’s moved. A hydrogen feasibility study with an outlook for Newfoundland and Labrador, and figures referenced by industry players and politicians alike, included in its “transformative scenario” a transition of just one of these tankers to hydrogen (or related fuel) by 2045.

There are other ships in local waters, like tugboats. The numbers are not large. It’s the kind of thing you can count on one hand for most of the Atlantic provinces—two hands for Nova Scotia. In September 2022, Svitzer (of A.P. Moller-Maersk) and EverWind Fuels, a leading proponent for hydrogen production in Atlantic Canada, announced a related memorandum of understanding whereby EverWind will provide “green fuel” (the exact type is not specified in company statements) from new infrastructure at the marine terminal for EverWind’s hydrogen-ammonia production facility at Point Tupper, Nova Scotia. On its side, Svitzer is to explore the procurement and retrofitting of a commercial tug for use in the Canso Strait. The stated goal is to have the first green fuel-powered commercial tug in Canada. In a joint statement, Svitzer’s head of decarbonization Gareth Prowse called it a “symbiotic relationship.”

“Developing vessels that can run on green fuels must be done in conjunction with the development of green fuels production and related fueling infrastructure. (…) We are excited to deliver on advancing green pathways for marine vessels in Nova Scotia,” Prowse said.

Parent company A.P. Moller-Maersk has been well into the weeds of the options for transitioning not just tugs but larger vessels. The company is a force in global trade, and in that role is at the centre of the ongoing determinations being made on what fuels will be on offer at ports around the world in the coming years. It’s another area where related infrastructure will need to be developed.

Ports are a mixture of public and private operations, with greatly varying ability to manage both the cost and spacial requirements attached to the evolution of marine power. And while major ports like Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, Europe’s second-largest seaport, can easily talk up the capacity for new fuels management coming onstream, the subject has barely been touched in many other jurisdictions. At the start of last year, Atlantic Business Magazine reported on work about the energy transition at ports in the region. In St. John’s, Saint John, Charlottetown, ports were generally waiting for signs of exactly where things were going, following news shared through associations like Green Marine, and making references to need for further development in technology and supply capacity. In Halifax, bunkering derivatives of green hydrogen was described by CEO Capt. Allan Gray as “a very strong possibility for us,” though he added more may be needed in hydrogen derivatives than liquid hydrogen, and the demand mix was really uncertain at this point. Gray suggested outright electrification would be unlikely, if trying to meet 2050 emissions reductions goals, given the time and cost tied to building out to provide enough electricity. Many Canadian ports still have no or limited ship-to-shore power, simply to allow vessels to run standby operations on something other than fossil fuels. When it comes to powering more, there are no easy or one-size-fits-all answers. At the same time, there is no clear indication yet of what ports in Atlantic Canada might—not will, but might—be capable of offering in liquid hydrogen, liquid ammonia, green methanol or other hydrogen derivatives, when, and at what cost.

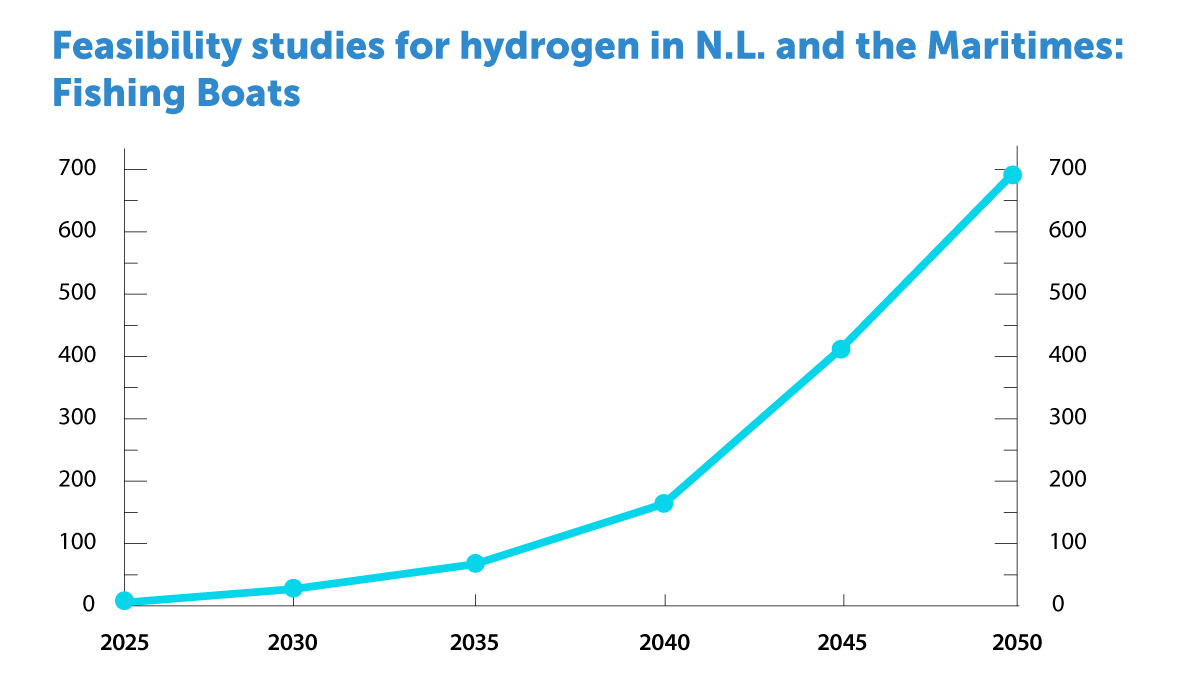

The hydrogen assessments for the Maritimes and Newfoundland and Labrador include aggressive scenarios, with 27 fishing boats using hydrogen by 2030 and just over 160 fishing boats by 2040, to about 700 by 2050. That’s out of about 12,000 fishing boats. The numbers are a shot in the dark.

A separate report released in early 2022 from the Centre for Ocean Ventures and Entrepreneurship (COVE) looked at the opportunity for electrification of over 20,000 marine vessels in Eastern Canada. One of the things it does flag is discussion of the use of ammonia to power vessels. It mentions “significant environmental and technical concerns,” but ongoing testing in Europe.

“Compressed hydrogen and liquid hydrogen fuel cells are leading the race for providing a path to decarbonization of larger vessels that battery electric systems cannot currently solve,” it stated.

For its part, in what it considers an ambitious rate of transition globally, Shell predicts hydrogen and related products could start to become mainstream in the 2030s. In a competing and less ambitious scenario, Shell estimates the timeline would be “slower by several decades.”

Planes

The Shell prediction for aircraft is no commercial alternatives to the status quo for jet planes emerge until the mid-2040s. That’s even if battery-electric starts to appear for “very short commuter routes” in the 2030s, posing competition for hydrogen fuel cell prototypes.

Future outlooks talk about meeting electricity demands for battery-electric planes, and of possibilities for more “sustainable aviation fuels” (SAFs), including fuels made in processes using hydrogen with carbon capture. The cost for these fuels is significant, but large energy companies, including Shell, are forecasting at least some drop in cost over time.

Right now, airlines are testing and looking around globally for all options. For the moment, electric isn’t ready for the longest hauls. There is a lot of mention of lowering emissions from status quo fuels, but not eliminating them.

That said, the future for planes may be the most important for would-be hydrogen suppliers and the hydrogen markets. Earlier this year, a look at possible hydrogen demands for Calgary suggested numbers for the Calgary Airport. “Assuming hydrogen replaces jet fuel as the zero-emissions aviation fuel of the future, and it has the same efficiency in energy use per kilometre traveled, the Calgary airport would need 480 t H2/day, 285 times more than that needed by ground vehicles.” The planes flying would be larger and carrying a lighter fuel.

NOTE: A previous version of this story included 2018 counts on locomotives in Canada. However, the counts from 2020 are the latest available and the piece has been updated accordingly.

Atlantic Business Magazine’s “Hydrogen Horizon” series is a high-level, moment-in-time look at the potential of hydrogen and its associated industry for Atlantic Canada. The level of demand for hydrogen production and the ability for Atlantic Canada to site competitive projects and service the markets, in a rapidly changing global energy sector, deserves serious and continuous evaluation.

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel