Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

Last in a nine-part series

The people of Atlantic Canada are just starting to hear more detail on a wave of possible wind-hydrogen-ammonia projects, with multiple proposals larger in scale than anything now existing in the world. In some cases, the projects are still taking shape or just developing a first phase. They’re being proposed as part of the energy transition and are tied to a company’s expectations for new demand. Of note across the board: projects are being aided not just by generally positive political talking points, but a genuine political push forward, with actions by governments to get regulations in place for launching green hydrogen production here, and significant tax credits to help financially. Atlantic Business Magazine reported on the federal credits earlier this year. But all in all, this isn’t normal business.

In fairness, governments want companies to be able to develop projects where they make sense, to stand on their own, bringing the region the big capital investments, employment and longer-term injections of cash into local areas through their operations. Big money, no whammies. Realists will understand there’s no guarantee these things will happen in every case.

It’s just hard not to see political cheerleading here. When EverWind Fuels completed environmental assessment for the first phase of its project on the Canso Strait in Nova Scotia, it was a celebratory day for the company. Premier Tim Houston also marked the occasion. “We’re leading the way here in #NovaScotia with a real plan for sustainable development and prosperity,” he posted to social media, with news of the approval. It’s not the kind of thing that’s at all unusual for a milestone day for a big, resource project in Atlantic Canada.

Newfoundland and Labrador’s premier Andrew Furey is steady-on with his own talk of local production and ammonia export potential. “Newfoundland and Labrador is well-positioned to produce green hydrogen due to its abundant developed and undeveloped hydro resources, surplus grid energy, strong wind resources, available Crown land and fresh water, deep marine ports, and proximity to markets in North America and Europe,” he said.

He attended the last World Hydrogen Summit in Rotterdam, Netherlands in May, promoting local development. That trip was also made by New Brunswick premier Blaine Higgs.

“There is no question we are building a true energy cluster, where we are leading the development and deployment of key technologies and setting the stage to attract more investment and opportunities,” he said in a statement.

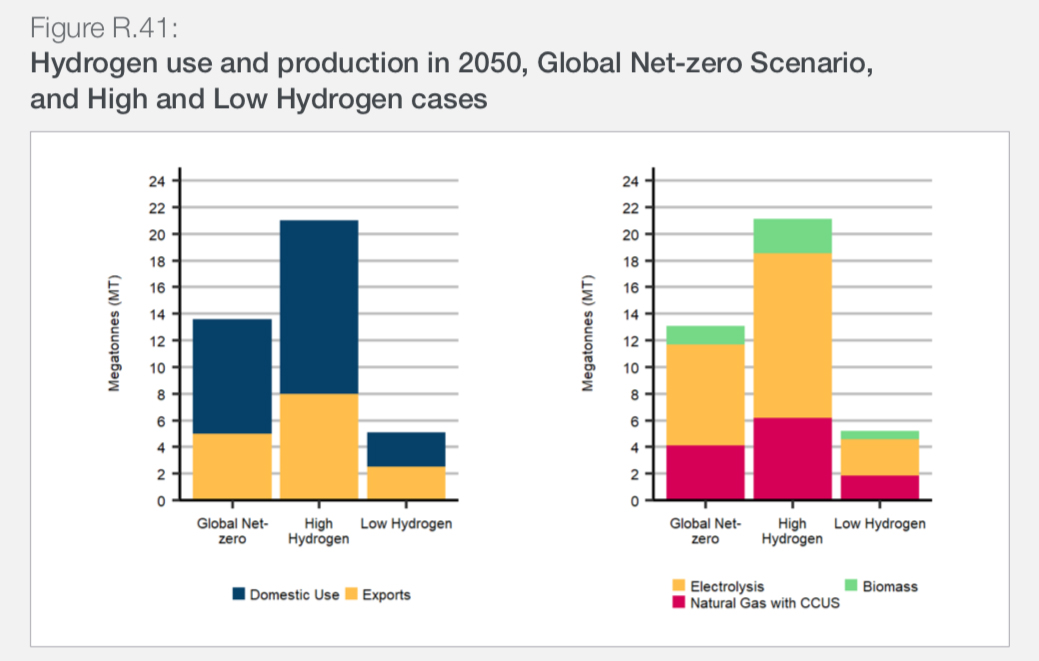

This week, after a year’s hiatus, the Canada Energy Regulator (CER) got back to its annual Canada’s Energy Future report. It’s one of the rare all-in-one outlooks from the federal government, putting numbers on the outlooks, including possible hydrogen futures. Hydrogen promoters will refer to the largest production figures, in a look-ahead scenario where the world is meeting its emissions reductions targets and getting down to net-zero emissions. In that optimistic scenario, Canada gets to 8 megatonnes (MT) of hydrogen exports a year by 2050. The assumptions behind that scenario include things like fuel cell truck costs being competitive with battery-electric and greater hydrogen use in shipping and aviation. It assumes the capital cost for electrolyzers drops 94%.

At the other end of the spectrum, in the “low hydrogen case,” our national exports are just 2.5 MT. It assumes fuel cell trucks are less competitive than battery-electric and the capital cost of electrolyzers comes down by only 15%.

There’s a third, “global net-zero” scenario that falls between the two. “In the global net zero scenario, we assume over 3 MT of hydrogen is provided by dedicated on- and off-shore wind electricity in Atlantic Canada. These exports use over 165 terrawatt hours (TWh) of wind electricity per year to produce hydrogen for export in 2050,” it states.

The scenarios can be world’s apart, but are all still possible futures. And they speak to the reality of a wide range of uncertainty right now on the predictions for uptake of hydrogen in different end uses globally, the overall demand and potential for sales.

In the near term, the CER sees hydrogen’s role in the Canadian energy system being “modest” until at least 2035.

Climbing the hydrogen ladder

If your head is spinning, as a starter, chemical engineer Paul Martin who has offered his thoughts on hydrogen recommends first dropping the “swiss army knife” image on hydrogen uses. That’s the image introduced in the first installment of this series, if anyone is trying to get a sense of the real potential. Along with chair and CEO of Liebreich Associates, Michael Liebreich, founder of BloombergNEF, he promotes thinking about the hydrogen ladders, where possible uses of hydrogen are weighed for their likelihood of taking hold. Think about what might drive real demand, and what might be interesting but ultimately fall to competition. If forecasts aren’t addressing market competition with battery-electric alternatives, for instance, or your political representative doesn’t speak to hydrogen’s market share versus suggestion of endless potential, it can become problematic.

Fundamentally, the business of hydrogen will have its limits, no matter the location, initial capital costs, secondary products and price points.

Liebreich recently appeared on the Mi’kmaq Matters podcast, hosted by lawyer and journalist Glenn Wheeler, speaking specifically to the Atlantic Canadian hydrogen-ammonia pitches at the Energy NL conference in St. John’s. “Most of the stuff being talked about at the conference, it’s probably not going to happen,” he said.

He didn’t discount the potential for one or more projects altogether. He did talk about energy losses in transport. He questioned why people here aren’t talking more about the need to transition fossil fuel-based hydrogen production in Canada. He also wondered about exporting a product made with renewable electricity from a region still trying to produce enough to meet domestic needs.

As for the idea of needing to build everything right away, taking the 250,000 tonnes a year of hydrogen proposed for production at the World Energy GH2’s development in western Newfoundland, Liebriech crushed any suggestion of hydrogen as an easy answer when it comes to climate change, saying: “That is 0.23% of global hydrogen. You would need 400 projects like that just to replace (just) existing, problematic hydrogen demand.”

A recent report from the Financial Times has suggested the push to a green hydrogen economy could require nearly 25,000 terawatt hours of renewable electricity a year, or 100 times current U.K. demand, to produce 500 million tonnes of green hydrogen a year. It would require spending roughly US$20 trillion by 2050. Currently, the report stated, “we are only about 0.15 per cent of the way there.”

Political promoters

The scale of what’s been proposed for Atlantic Canada will see more attention in the years to come. Last summer, Shell announced a final investment decision, pressing ahead with Europe’s largest green hydrogen plant, Holland Hydrogen I. Now under construction, the plant is expected to be operational in 2025. That’s a familiar date—matching a goal stated as part of the Canada-Germany Hydrogen Alliance signed in Stephenville, Newfoundland and Labrador last year and begs some review.

Shell is certainly familiar with hydrogen. Per company statements, it owns and operates around 10% of the global capacity of installed hydrogen electrolyzers, including operations in China and Germany. Europe’s largest green hydrogen facility is being built next door to Germany, in the Netherlands, right at Rotterdam. Electricity will come from a roughly 760-MW offshore wind farm, located less than 20 kilometres off the coast. The wind farm is partly owned by Shell.

Construction on the wind farm started in October 2022 and is set to be complete by the end of this year. Shell’s facility is set to produce 60,000 kilograms a day of hydrogen. That’s 60 tonnes. If running every day of the year, that’s 21,900 tonnes a year. EverWind Fuels has suggested 200,000 tonnes a year will be coming from its Canso Strait facility in its first phase. World Energy GH2 has said 250,000 tonnes a year from its first phase. In its last available posted information, Pattern Energy pitched a more modest 88,000 tonnes per year from its start at the Port of Argentia. The list goes on.

That’s not to say there are no similarly large pitches for new production facilities in other parts of the world to match those in Atlantic Canada. But the discussion on scale of all of these proposed projects in the region combined is a discussion in itself.

Exporters have to compete

It should be kept in mind that not only is the amount of hydrogen demand for our trucks, ships and planes undecided, but it can be produced by everyone, everywhere. Cheap solar units and less-cheap wind farms (still far less expensive than a decade ago) make that possible. There are some very large, existing hydrogen production facilities not using renewables that may incorporate more. There is more production being proposed at manufacturing sites of all kinds. And while it would be a smaller club of hydrogen and ammonia producers if we were demanding it all be made solely from renewable electricity, that’s not realistic right now given global energy demands.

It’s true that markets are expected to grow, even if the rate is sometimes oversold, but most importantly producers still have competition. As much as Atlantic Canadians have been hearing about local “green” hydrogen production being at the forefront, the same is being said in other parts of the world.

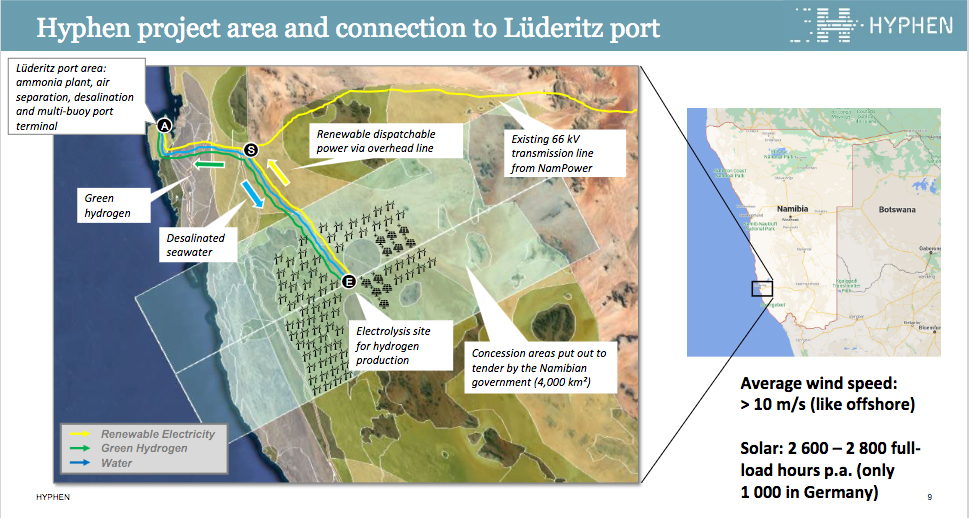

In Namibia, as an example, conglomerate Hyphen Hydrogen Energy is developing a more than $13 billion (US$10 billion) hydrogen-ammonia project. A first phase is expected to see about 175,000 tonnes of hydrogen and as much as one million tonnes of ammonia produced each year. If fully developed, that will climb toward a target of 350,000 tonnes of hydrogen and similarly greater ammonia. And it’s realistically in line with the timelines for some of the early movers in Atlantic Canada, with construction expected to start in 2025.

China may be looking at demand for hydrogen estimated up to 100 million tonnes a year by 2060. That is a tremendous amount. However, as Upstream recently reported, the country can also start to feed its own needs by sourcing from inside its own borders. It is already reported to be planning to build new solar and wind farms in the country’s North and Midwest, producing hydrogen there, working with existing refinery and chemical plants in the same regions. It plans to pipe hydrogen into a 6,000-kilometre-long network running to larger centres outside the industrial regions.

Atlantic Canada offers ports that are marketed as being close to Europe but what is close? Pipelines are being proposed for connecting European producers to hydrogen transit capitals like Rotterdam, and Scandinavian countries are also eyeing the German market. The Finnish government is looking at national hydrogen infrastructure. Denmark is looking at the possibility of large-scale exports to Germany. In Norway, as a more specific project example, Provaris Energy and Norwegian Hydrogen AS have completed a pre-feasibility study on a 50,000 tonne-per-year green hydrogen production facility, with production scheduled for 2027.

Atlantic Canada has powerful winds, but a sun-wind combination in parts of Africa, South America and Australia could prove even more potential as a power source. And a cargo run from the Port of Casablanca, Morocco to Rotterdam, Netherlands is shorter than a cargo run from a port in Atlantic Canada to the same (roughly 1,680 nautical miles versus 2,420 nautical miles).

Question time saw @SophieScamps quiz the government on #Budget2023's $2 billion hydrogen investment.

Hear @Bowenchris respond ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/4PwX0OYggU

— SmartEnergyCouncil (@SmartEnergyCncl) May 10, 2023

Saudi Arabia is producing hydrogen, aiming to be the world’s cheapest producer overall. Purdue University engineering technology professor John Sheffield suggested in an emailed response to questions the country has at least 46 viable hydrogen projects, worth about $92 billion. And a deal to establish what’s been dubbed the world’s largest green hydrogen plant to date (it’s a moving target), located in Oman, is expected to be announced any day according to several energy industry publications.

In Canada, there are hydrogen-ammonia projects coming in all provinces aiming to serve emerging domestic and international demand. Some are also looking at shipping more advanced products made with hydrogen, as with the Canadian Methanol Corporation’s proposed Tumbler Bridge Methanol Project for blue and green methanol in British Columbia. In Alberta, there are projects like the Crossfield Hydrogen Hub. Construction has also started on the $1.6-billion Air Products facility producing hydrogen, possibly serving a new renewable diesel facility as an early customer. In Saskatchewan, Linde is proposing to use new hydrogen production to feed a proposed “net zero” Dow Chemical plant making ethylene in Fort Saskatchewan. In Quebec, an area driving hard toward green ammonia as much as Atlantic Canada, a Hy2Gen Canada project with a 210 MW power requirement, producing 173,000 tonnes of green ammonia a year is due to be shipping in 2026. These are just a handful of the examples with final investment decisions expected in the next five years.

For weighing your fit in potential markets and market demand, timing can be everything. Consider that Norway’s MF Hydra ferry, a test case watched by ferry operators around the world, is fueled by hydrogen from Germany—the very place people are told is in desperate need of hydrogen right now. It’s largely a matter of timing. Germany is ramping up quickly in its green hydrogen push, but at the time the Norwegian ferry operator Norled was looking for a liquid hydrogen supplier, the German production was not spoken for, opening the door to an export supply contract.

Icelandic dreams and Swedish mists

It has largely been forgotten now, but in 2006 Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro executive Jim Keating encouraged Newfoundland and Labrador premier Danny Williams to visit a hydrogen fueling station, while Williams was on an official trip to Iceland. On the heels of the trip, Williams was described in government communications as, “very keen to learn more about the alternate technologies being developed in Iceland, specifically in hydrogen energy.”

“They are leading the world in innovative energy expertise like hydrogen technology. It was amazing to see the progress they have made in that area, and I am excited by the potential for hydrogen technology in our province,” the premier was quoted as saying, with a note information gathered on the trip would feed into the then-ongoing development of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Energy Plan.

However, hydrogen was not mentioned in the plan, other than in relation to a single research and development project by Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro looking at a wind-hydrogen combination to serve isolated electricity grids. There was nothing related to other possible configurations involving hydrogen for isolated grids, hydrogen for transportation, to production of ammonia, basics like hydrogen containment, hydrogen or ammonia shipping and handling. And there were no follow-up electrical utility test projects by the Crown local, the province’s main power producer, after the project at the isolated community of Ramea, on the island’s South coast, wrapped up in 2010.

Even with the premier’s visit, Iceland’s advanced investigations of hydrogen never crossed the water. And Williams wasn’t the only one in Atlantic Canada familiar with them.

It’s a different and still-changing world today, with the ability for remarkably cheaper power production even from 2007, but it remains a standing question: do local concepts for production and export of ammonia make sense for investors?

Hydrogen has proven to be an area of ups and downs, where politicians have quickly flipped in the past from full-throated support to relative silence, even within a single administration.

In the private sector, there is hydrogen hype internationally right now. If you don’t think so, you’ve probably missed related marketing campaigns, like the “industrial emissions face mist” promotional event from European energy company Vattenfall. Their mist allowed people to spritz themselves with wastewater from a Swedish factory making fossil fuel-free hydrogen. The mist was not a product for general sale, but the company states a few bottles were actually produced for a marketing campaign, carried by actress Cara Delevingne in online ads.

Atlantic Canadians are hearing about hydrogen quite a bit in daily news coverage, but we’re still a long way from having a clear picture on the extent of wind-hydrogen-ammonia developments in the region by mid-century.

For their part, governments have been part of photo ops based on early-stage private industry “memorandums of understanding” (MOUs) they are not a direct party to, and MOUs they are a party to but that are worded generally enough as to be immaterial for all practical purposes. An agreement to simply “cooperate” in the coming years on evaluating opportunities means very little in the grand scheme of commercial activity ongoing around the world. And it’s always important to remember that there are typically no penalties set for a government failing to “cooperate” as promised, should political tides turn.

And there is no penalty to Canada if we do not have hydrogen-ammonia projects shipping out ammonia to Germany by 2025.

Atlantic Business Magazine’s “Hydrogen Horizon” series is a high-level, moment-in-time look at the potential of hydrogen and its associated industry for Atlantic Canada. The level of demand for hydrogen production and the ability for Atlantic Canada to site competitive projects and service the markets, in a rapidly changing global energy sector, deserves serious and continuous evaluation.

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel

Unfortunately on Nov 16 colchester cty fell victim to hydrogen hype by the equity fund former Blackrock partner T Vichey now ceo of Everwind. Champing at the bit to destroy 34k + acres & similar tracts in Hants & guysbough cty w/ turbines using underpowered NS grid to Pt Tupper that the feds just handed over 125 million for plant conversion. Another “Atlantic canada’s fiascos & boondoggles “ story And we r no further decarb our own grid & much diminished carbon holding forests & wetlands – all before colchester cty & NS have finished their new land use plans