Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

Third in a nine-part series

Releasing the Hydrogen Strategy for Canada at the end of 2020, leaders at Natural Resources Canada said it was a “call to action” for the country, to not just grow production and use of hydrogen but fundamentally establish Canada as a hydrogen economy. In truth, that call came decades ago, through scientists highlighting the damage of fossil fuels and pointing to hydrogen as part of the response. There was even a specific call in the 1980s for landmark support to see Canada “first to the Hydrogen Age.” Theoretically, we’d be comfortable by now with electrolyzer manufacturing, production at scale, availability of end use machinery. In reality, we should at least have a better handle overall on real opportunities under the hydrogen umbrella, versus hype. Limited action decades ago, paired then with years of on-and-off government support for research and development (R&D), has left us strained.

Atlantic Canadians are bombarded now with endless comments on the urgency of decisions on hydrogen projects. They’re told about the need for new hydrogen and ammonia manufacturing at world-leading scale, but with governments at the same time still scrambling to, among other things, affirm related regulatory standards and settle permitting processes. In one breath, the word is we need to fast-track projects to have exports in less than two years. In the next, there are barriers for hydrogen in innovation, economics, policies, codes and standards, even awareness of markets and basics on safety.

Seeing the history, it makes the point that political will and financial support can come and go. It’s also an example of how decisions on political attention and spending on any given day really do shape the future.

The romantics

Looking back, from the recording of hydrogen as a distinct element in 1766, through scientific papers and prototypes of all kinds, eventually there were chemists and engineers, systems specialists, who wanted a broader discussion on hydrogen as an energy source, beyond any one invention. And they were around earlier than many might think. In a fossil fuel-addicted world, they viewed hydrogen as a way out, or at least part of more diverse energy systems. By the 1970s, Australian electrochemist John Bockris made one of the earliest references to the idea of a “hydrogen economy” in his published work.

Globally, things really kicked off in March 1974, at a gathering at the Playboy Plaza Hotel at Miami Beach, Florida—a venue frequently hosting Hugh Heffner himself. At the time, the hotel was booked for the sake of its available rooms and cheap prices. The Hydrogen Economy Miami Energy conference was a first-of-its-kind. The chairman was an engineer, Turhan Nejat Veziroğlu, based at the nearby University of Miami, where he’d founded the Clean Energy Research Institute and new motivation in the wake of the 1970s oil shocks. Veziroğlu and his team were years into investigation of clean energy sources, finding energy storage and portability remained a particular challenge. It led them to work in alternative fuels and, ultimately, hydrogen.

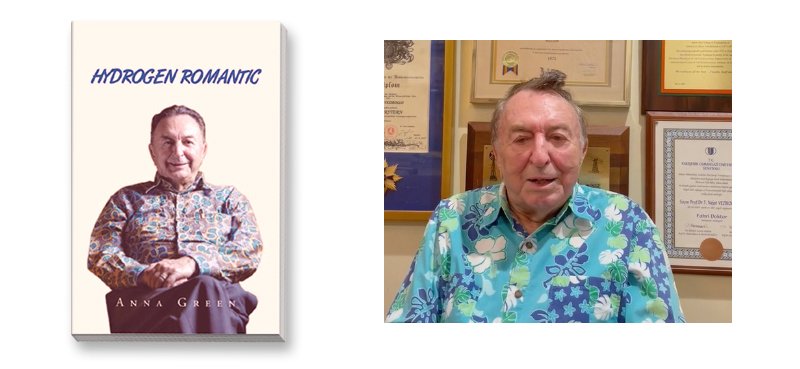

The professor managed to land $70,000 from the U.S. National Science Foundation to support the conference. As he would later describe for the book Hydrogen Romantic, with no social media or email chains at the time, he worked long hours with a handful of secretaries to mail brochures and letters out one-by-one to engineering and energy-focused departments around the world. The conference ended up having more than 80 countries represented. And, at a gathering on the first evening, a group of 11 engineers, all like-minded people, who Veziroğlu later dubbed the “hydrogen romantics,” agreed to establish an association. The International Association for Hydrogen Energy formed. Veziroğlu was its first president.

The first World Hydrogen Energy Conference followed in 1976, gathering researchers, this time with an even broader added cast of environmentalists, industry reps and politicians interested in the potential in hydrogen. And Veziroğlu spearheaded the launch of the International Journal of Hydrogen Energy that same year.

Early Canadian leadership

Canada was in the mix of hydrogen innovation happening through much of the 20th century. The country was actually viewed as an early global leader in related R&D. Looking back, there were pioneers in practical applications like Alexander T. Stuart, who started by looking at ways to make use of excess hydroelectric power. His Stuart Cell became a world-leading electrolysis system (splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen). Commercialized in the 1920s, a Stuart system ended up in more than 100 countries. Stuart and his descendants would land over 50 novel patents in hydrogen-related tech.

In 1981, a parliamentary committee looking at fossil fuel alternatives recommended Canada invest in more hydrogen research and develop more production capacity. And with what seemed a wide variety of ongoing research needs relating to hydrogen—anything from containment standards to practical end-use, hydrogen-powered tech—the Government of Canada funded an R&D program. It was run by the National Research Council (NRC), with tentacles reaching into several departments. It included projects with private industry partners. An Institute for Hydrogen Systems was also launched around this time in Ontario, with the financial help of the provincial government there. But it was always two steps forward, one step back. The federal research program was all but eliminated in the 1984 federal budget, while the Government of Ontario ended its support to the Institute for Hydrogen Systems within two years of launch.

In our history, if there was something to refer to as “the” call to action for Canada on hydrogen, it came then—36 years ago—in a report of the National Advisory Group on Hydrogen Opportunities. The group was a federal, blue-ribbon panel, called together by the government after the slashing of the federal R&D program drew complaints.

After two years of investigation, the nine advisors making up the National Advisory Group on Hydrogen Opportunities pressed one, central recommendation in their final report in 1987: “Canada should adopt a national mission to position itself to be the first to the Hydrogen Age.”

They offered detailed rationale, and next steps. They didn’t talk about hydrogen as a fuel in competition with other fuels. They instead opted to write about climate change, and a future where they advised oil and gas use would be constrained as a result of greenhouse gas emissions. They suggested electricity and hydrogen—the latter as a product made with electricity that you could package up in different forms, transport long distances and make use of in heavy industry—would eventually become global currency.

They proceeded to tell Parliament that there was at that point, “no significant Canadian activity to develop hydrogen-fuelled products for transportation or stationary applications” and “no significant Canadian activity to develop technologies for hydrogen distribution, storage or refueling.” Their report to Canada’s Minister of State for Science and Technology and Minister of Energy Mines and Resources—Brian Mulroney’s cabinet fellows Frank Oberle Sr. and Marcel Masse—stated a global move to hydrogen was already started. The pace was slow, but the real question was when the change would speed up and become obvious to people in all countries. They reported, by their assessment, it was just a matter of Canada deciding if it wanted to get out ahead and capitalize on what was coming, or scramble years down the line.

Moonshot down

Air quality and fears of limits on fossil fuel supply were still common topics of discussion at the time but climate change was actually central to the report. The advisors offered the Canadian government a couple of clear ‘what if’ scenarios for the future.

In the first outlook, they suggested, at one end of the spectrum, people decide to all but ignore environmental effects of status-quo use of fossil fuels. Canadians would live in a “fossil fuels forever” world. In this case, a landmark effort like the one the advisory group called for would still offer Canada new technologies with applications in the oil and gas sector, with capabilities to cut the rate of fossil fuel reservoir depletion, maximizing use of our finite resources. In a fossil fuel powered world, hydrogen could offer opportunities in hydrogen made with natural gas.

There was alternatively a second scenario. “Assume world geopolitics becomes driven by concern for catastrophic global climatic changes caused by atmosphere CO2 from the combustion of fossil fuels. The world must wean itself from fossil fuels as quickly as possible—and during that weaning emit the minimum CO2 to the environment. Simultaneously the world must develop non-fossil sources of hydrogen and, most importantly, a full matrix of new hydrogen-fueled products,” they stated. A prolonged hydrogen push would pay dividends either way.

The panel wasn’t packed with environmentalists or representatives of activist NGOs. It wasn’t full of what former Alberta premier Jason Kenney might have labeled “anti-Alberta energy” voices. It was arguably Alberta oil and gas heavy, with the ranks including Clement Bowman (d. 2021), a senior researcher with Syncrude Canada and Imperial Oil, and a founding chairman of the Alberta Oil Sands Technology and Research Authority (AOSTRA). He was vice-president of Esso Petroleum at the time.

It also included John Masters, president of Canadian Hunter Exploration Ltd., who in 1976 discovered the Elmworth natural gas field in Alberta. In his 2011 obituary, Masters was described as “one of the last great oilmen.”

“The only realistic way to deflect the impact of the greenhouse effect is through the use of sustainable energy sources…”

—National Advisory Group on Hydrogen Opportunities, 1981

Beyond oil and gas, the panel included Alexander Stuart (d. 2014), who had followed in his father’s footsteps and was both the president of Electrolyser Inc. and chair of the International Energy Agency’s hydrogen executive committee. There was Lionel Boulet (d. 1996) who taught electrical engineering at Laval University and consulted for Hydro-Québec, before becoming the first director of the Institut de recherche d’Hydro-Québec (IREQ), an institute launched with some federal assistance on the heels of the breakthrough creation in Quebec of 735-kv electrical transmission lines. There was vice-president of the SNC Group, Réal L’Archevêque (d. 2018). The panel also included vice-president of Atomic Energy of Canada George Pon (d.2011), and C.D. Howe Institute founding executive director Carl Beigie (d. 2010), working as a chief economist with Dominion Securities in Toronto. The two surviving members are former Progressive Conservative MP Gordon Gilchrist, who served as a critic in the House of Commons on the Science and Technology portfolio. Finally, there was chair David Sanborn Scott, a professor of engineering at the University of Toronto at the time, founder of the Institute for Hydrogen Systems. He headed from there to the University of Victoria, where he continued work on energy systems.

Collectively, they were crystal clear in their comments. As they reported nearly 40 years ago, the emphasis here being theirs: “The increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, resulting from emissions of the fossil age, will lead to global climatic changes (commonly called the greenhouse effect), which may become catastrophic to the orderly growth of civilization. The only realistic way to deflect the impact of the greenhouse effect is through the use of sustainable energy sources manufacturing the two renewable currencies electricity and hydrogen.”

When they filed their report, their thinking included concern over the possibility of shortages of fossil fuels but, as Scott would go on to emphasize, including in a 1991 presentation on “The Emerging H2 Age” for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the main driver quickly instead became climate change.

“The issue is that if we burned all the fossil fuels we now know exist, the planet is uninhabitable (…) Fossil fuel is capped by the environment. It is not at all capped by resources,” he said.

He repeated the point time and again, including in his 2007 book Smelling Land: The Hydrogen Defense Against Climate Catastrophe, where he also addressed things like the suggestion rising oil prices could change the long-term view. “We can take no comfort in hoping that prices will rise to cap fossil fuel use before CO2-induced catastrophe,” he stated, pointing to the scale of fossil fuel dependence and greenhouse gas emissions.

For any success in a national mission on hydrogen, the panel said Canada needed leadership at the federal level and “continuity of political support for at least two decades.” An early step, they advised, would be to create a Canadian Hydrogen Authority (similar to how the U.S. created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration), that would be a political champion for the mission to transform our fossil fuel-centric country. They suggested $50 million in funding from the federal coffers over five years. But their report was shelved.

Around budget time in 1988, New Democratic MP Howard McCurdy moved the government “consider the advisability of” introducing legislation to establish the Canadian Hydrogen Authority, starting on work with industry, academia, labour and others in setting exact targets, projects and timelines for the more ambitious elements. He also spoke of it in the context of climate change. “If it continues at the present rate, it will drastically alter the climatic conditions and cycles of the entire planet by the middle of the next century, if not before. It means massive flooding or droughts and drastic changes to crop conditions around the world,” he said.

In debate, Progressive Conservative MP Gary Gurbin said the government was interested in seeing the private sector develop technologies (ignoring calls from the private sector—including some on the hydrogen advisory panel—for a sustained, coordinated, government-led push to help make progress). His caucus fellow, MP William Tupper, questioned how much money McCurdy would dedicate to the hydrogen idea, skipping past the advised budget.

McCurdy and the NDP wouldn’t have to manage any national mission. Yet, he was one of the few to ever lay out the scale of the call to action in the House of Commons. “A national mission is quite different from an area of emphasis. There is any number of areas on which we can have some emphasis. There are certainly possibilities for smaller, more narrowly defined missions. But none can take the measure of the type of national mission that is conceived of in this proposition. It challenges the imagination with respect to what it is capable of doing. It will generate new science, new industry and new engineering,” he said. It also allowed for a federal body that would track work, advise, theoretically avoiding things like repetitive subsidies.

The debate on it all was short-lived. The Hydrogen Authority was never established, and the national mission was never undertaken. Individual projects recommended in the report of the blue-ribbon panel commission stayed on paper.

At the time, in May 1988, a letter from Veziroğlu—the organizer of that early hydrogen conference in Miami—was published in the New York Times, carrying the headline: “We’re not condemned to carbon-based fuels; change to hydrogen.” He reiterated the idea of a move to more hydrogen, including production of hydrogen using hydroelectric power in Eastern Canada.

“If we change our energy system from the fossil-fuel system to the hydrogen energy system, there would be little or no pollution, little or no acid rain, and as a bonus, the greenhouse problem would also disappear,” he wrote.

He wrote again the next month, this time directly addressing what was the clear hurdle of financial cost of hydrogen made with renewable energy sources. And he wrote: “The hydrogen produced will cost two to three times the price of petroleum. But when you take the damage caused by carbon dioxide, pollutants and acid rain into consideration, hydrogen becomes much cheaper.”

He and others like Scott, the Canadian advisory group’s chair, never relented. Atlantic Business Magazine sought to speak directly with Veziroğlu, but after a series of recent health challenges, as his wife Ayfer conveyed via email, his health did not allow it. She is also a researcher, with a career spent digging deep into hydrogen powered systems, and has authored more than 20 peer reviewed papers and multiple books, including Hydrogen Powered Transportation in 2017. There was no response to email requests to Scott for an interview.

On Ballard and benefactors

Even without grand plans and government support, some progress has been made relating to hydrogen production and its use in Canada since the 1980s. There have been influential private industry leaders, with Ballard Power Systems, founded in 1979, sitting at the top of the list.

As B.C.-based writer Tom Koppel describes in Powering the Future: The Ballard Fuel Cell and the Race to Change the World (1999), Ballard’s advancement of proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells and hydrogen fuel cell stacks was helped along by contracts with a small fuel cell group started within Defense Research Establishment Ottawa (DREO; now Defence Research and Development Canada). Notably, the funding for DREO’s projects came in part from the federal government’s sporadic, early-1980s support for hydrogen R&D. When the hydrogen funding was slashed, in Ballard’s case, the Department of Defense did step in with some select funds for a few, additional contracts, out to at least 1989. Quoting a chemist responsible for some early Ballard contracts, Koppel wrote that without the early government money for R&D, the later projects “probably never would have happened.”

Ballard teams advanced the makeup of fuel cells over time through R&D and commercial demonstration projects, making them cheaper to produce and more effective once available. It’s the kind of work that takes time and money. The company fought on through the ups and downs through the years. And it’s curious to think what the company’s journey, and that of others like it, might have been like if Canada had followed the recommendations of the National Advisory Group on Hydrogen Opportunities or otherwise sustained R&D funding.

New rush to research

At the NRC, programs advisor for Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies François Girard is surprised at anyone knowing much about hydrogen-related efforts before the 1990s. At the top of a recent interview, he made a point to say he isn’t interested in getting political about R&D funding but acknowledged the history of hydrogen R&D in Canada (activity based on both public and private capital) has been “cycles of up and down” and “a lot of stop and go.”

He started with the NRC during one of the “go” periods, being a surge in support starting at the end of the 1990s. In 1999, the NRC, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) and Natural Resources Canada jointly announced a “Hydrogen Fuel Cell Innovation Initiative,” each putting $1 million on the table for hydrogen fuel cell activities. From there, the NRC started its own national fuel cell program that ran until around 2010. “Then we had the change of government, which kind of slowed down a few of our things, but we kept on going with some research programs, especially around transportation,” he said.

More broadly, there was a federal “hydrogen economy program” to the tune of about $170 million, running for five years but then ended as planned. And the ups and downs never went away.

But there has been no “up” like the period since the release of the new national hydrogen strategy for Canada. In the last few years, Girard said, things “really took off big time.”

At the NRC alone, staff are into anything from the grind of hydrogen-related core science research to more advanced work on end use applications. They’re investigating technologies proposed to reduce the cost of making green hydrogen (specifically the cost of electrolysis); potential for more efficient hydrogen liquification; integration of hydrogen fuel cells into isolated rural microgrids in Canada; “fairly rapid evolution” for alternative fuels in aerospace; limits on mixing hydrogen with natural gas; materials for hydrogen pipelines; and—in what people are likely to hear more about—any gaps in codes and standards related to hydrogen production, transport and exports. Hydrogen is a pillar in NRC’s advanced clean energy programme.

“The intensity of activity at NRC on hydrogen technologies today is definitely much larger than it was in early 2000s and I would guess larger than it was in the ‘80s,” said Girard.

Guided by an expectation of growth in hydrogen production across Canada, the NRC is deep into work on the technical details of existing and proposed pathways to produce hydrogen. Staff dig into capabilities of individual components, offer accepted means for accelerated testing and work with industry partners on tabletop reviews to help troubleshoot novel projects.

“The emphasis now given the hydrogen strategy publication and so on has been more and more about the ability to produce hydrogen at large volumes,” Girard said.

Government researchers are not alone of course. There is joint research and private research, with private investors also directing more money now into post-secondary institutions. It’s not just within Canada. There is more money flowing across borders, through partnership projects. In Canada, some of the post-secondary research players are longstanding, working on hydrogen R&D projects through the decades as best they could. There’s the Hydrogen Research Institute (IHR) at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, but others grabbing more and more of the headlines now, like the Clean Energy Research Lab at Ontario Tech University and the Clean Energy Research Centre at the University of British Columbia (UBC). UBC’s more than $23 million Smart Energy District, a city-block-sized research hub with one part being a hydrogen refueling station integrated with a solar-topped parking garage, broke ground back in 2021 and, in April, welcomed German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier (in case anyone thought Atlantic Canada had any kind of monopoly on German attention). The project is led by professor of mechanical engineering and associate dean of research Walter Mérida. Again, echoes of the past, as Mérida began in clean tech through work with the likes of the NRC and Ballard Power Systems. In an opinion piece for the Hill Times, after release of the national hydrogen strategy, Mérida said there was room for improvement but preached the strategy, “is another step towards the inevitable decarbonization of our energy system.”

Increasingly, hydrogen-related R&D projects are being supported by provincial spending as well, with provincial agencies directly servicing industry needs, such as the Alberta Innovates Hydrogen Centre of Excellence. It recently awarded 18 hydrogen-related projects more than $20 million.

“Hydrogen activity has gone through some ups and downs over the years,” said mechanical engineer and University of Prince Edward Island Vice-President, Academic and Research Greg Naterer.

Naterer has been active in work relating to hydrogen for decades now. He’s seen work that has, among other things, managed to bring down costs on promising technologies such as the copper-cycle of hydrogen production. Naterer says a better public understanding of what is possible, and what it costs, can come through public demonstration and pilot projects. He suggested people might be surprised to learn basics like the fact the clearest opportunities for hydrogen have nothing to do with your car (more on that in the next installment of this series).

“Actually the most promising place where hydrogen is most beneficial is larger vehicles. So planes, trains, ships,” he said. And while it’s true hydrogen-powered is competing with electric-powered and other alternatives, all options have their limits, and pros and cons from a business perspective. It’s a standing question as to what portion of the end use market hydrogen options will capture, and so a question as to how much demand for hydrogen will arise and, swayed largely by political and public interest, what local communities can expect to see.

Essentially, Canadians can expect to hear more about hydrogen in the coming years, from the labs but also beyond them. New demonstration projects will eventually come to communities in Atlantic Canada. They may involve in rare cases landmark R&D, technical testing on well-understood machinery specific to the environments here, work on technical standard setting, or there may even be some as marketing maneuvers. Regardless, it’s all fast and furious now, rather than spread out over a longer period of time. We are facing down goals like green hydrogen (really, ammonia) exports to Germany by 2025, and the keystone of a net zero Canada by 2050. Not everyone is “for” hydrogen, but we’re all going to continue to hear about it.

Atlantic Business Magazine’s “Hydrogen Horizon” series is a high-level, moment-in-time look at the potential of hydrogen and its associated industry for Atlantic Canada. The level of demand for hydrogen production and the ability for Atlantic Canada to site competitive projects and service the markets, in a rapidly changing global energy sector, deserves serious and continuous evaluation.

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel