Account Login

Don't have an account? Create One

Fourth in a nine-part series

Hydrogen concept cars have been painfully slow to translate into showroom staples, with good reason.

Right now, even when consumers are willing to pay more for a zero-emissions vehicle (ZEV), hydrogen vehicles are struggling to compete with battery electric (what people commonly call EVs) and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs). Hydrogen cars and trucks (a.k.a. fuel cell electric vehicles, FCEVs) are only a small fraction of the growing ZEV market. And, when they are available, they come with the added challenge of a lack of fueling stations and close-to-home service.

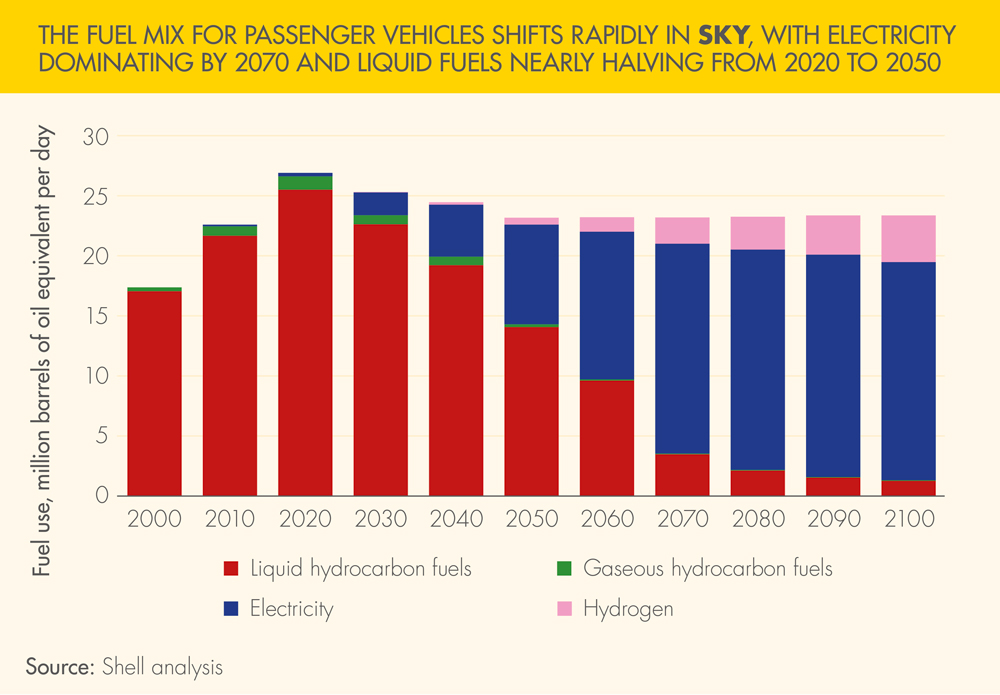

In terms of energy efficiency, using electricity to create hydrogen to then fill up a fuel cell vehicle is fundamentally less efficient than directly charging an EV. And pressing for growth in the number of hydrogen-powered vehicles without knowing where the hydrogen fuel will come from risks creating new hydrogen demand, filled by hydrogen manufactured in a way that could ultimately add to greenhouse gas emissions, rather than reduce emissions. And while more and bigger EVs will be a challenge in terms of availability of critical minerals and need for mining, the EVs are far out in front for light-duty vehicle demand.

If hydrogen cars are pursued in Atlantic Canada, it’s still unlikely the market here will be a source of much demand for hydrogen for decades to come. That’s based on things like vehicle turnover rates, total vehicles in the region and need for related infrastructure, including refueling stations, to allow cars to roll off dealer lots.

Prototypes and press conferences

Operationally, as the U.S. Department of Energy describes it, hydrogen fuel cells, “work like batteries” that don’t run down or need charging, they just need liquid hydrogen. In a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle, hydrogen molecules are separated into protons and electrons in an electrochemical reaction. There is a flow of electricity, and the end product out of the reactions in the cell is water. A single fuel cell doesn’t offer much juice but fuel cell stacks, with hundreds of cells, can create a power system for a car, to get you where you’re going.

Foundationally, hydrogen-powered cars and trucks have existed for many years. A prototype “car” powered by hydrogen gas, to be very generous in the context of modern vehicle standards, existed as far back as 1807. The modern start for the hydrogen car came with a high school science fair project by American Roger Billings, who eventually converted his father’s Model A Ford to run on hydrogen. Billings was still a freshman in college when he was funded by Ford for further research, ultimately staking his claim as the father of the hydrogen fuel cell car. Different demonstration models produced with colleagues followed.

Hydrogen and fuel cells captured greater public attention on the heels of the OPEC oil embargo in the 1970s. The U.S. wasn’t alone in the investigation of hydrogen cars at the time. In 1973, the Hydrogen Energy Systems Society of Japan was created. Researchers at the Musashi Institute of Technology in Tokyo unveiled the Musashi 1 car the next year and, supported by Japanese automakers, developed one new vehicle design after the next. Other prototypes popped up globally.

There was new attention in response to smog complaints in major U.S. cities. Consumers read about hydrogen vehicles in their newspapers and saw them on television, as when Hollywood star Jack Nicholson took part in a press conference for Chevrolet in 1978, talking up the environmental benefits of the H2-4 Chevy hydrogen-fueled car. When CBC plucked footage of that presser from its archives a few years ago, it introduced many Canadians to a 1970s-era hydrogen car for the first time. That’s because, for decades, hydrogen cars never actually appeared for sale.

From press conference to driveway

On Dec. 3, 2002, nearly a quarter century after Nicholson’s promotional work, a Honda FCX fuel cell vehicle had its moment. One of the cars was delivered to the official residence of Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, while a matching car went to Los Angeles Mayor James Hahn at City Hall. Los Angeles committed to lease five of the vehicles, for city employees. The leases were marked the world’s first commercial application of a modern fuel cell vehicle, holding the first permit for commercialization in the U.S.

That said, having the ok for a sale doesn’t necessarily get you to mass production and cars rolling off of sales lots around the world. As the Japan Times reported, an American Honda executive was clear in 2002 there were still cost and infrastructure issues to work through before the vehicles could, practically speaking, be mass marketed. For years after Honda’s landmark approval, only about 30 Honda FCX vehicles were reportedly going to be deployed in California and Tokyo. In the U.S., two years on, a couple of the cars had been leased by the City of San Francisco, one went to the City of Chula Vista, also in California, and a pair went to the state’s South Coast Air Quality Management District. The State of New York became the first state in the U.S. to directly join in, leasing two of the cars.

One of the clear issues for uptake of vehicles like the Honda FCX was the lack of refueling infrastructure, or essentially the need to rapidly add something equivalent to the gasoline stations dotting U.S. highways. People wanted at least some distributed service centres.

It’s worth noting that in 2005, when Honda let one of its cars as a family vehicle for the first time, specifically to the Spallino family in California, they were chosen in part because they lived near the company’s refueling station. The Spallinos were also one of the few families already in a leasing program for a relatively rare natural gas-powered Honda Civic. They were offered lease of their Honda FCX at $500 a month, according to the New York Times, while the car itself was estimated at the time to be worth about US$1 million (hydrogen vehicle costs have come down significantly since, but still aren’t a match to electric or hybrids).

Zero emissions eventually

The first hydrogen fuel cell vehicle mass produced and widely sold is the Toyota Mirai, a sedan launched in 2014 in Japan and 2015 in the U.S., and still on the market today. “Mirai” means “future” in Japanese. When launching the Mirai, Akio Toyoda pointed to a key selling point against electric options, saying it could refuel in just five minutes. He inadvertently showed another weakness for hydrogen vehicles, in mentioning fuel.

“We imagined a world filled with vehicles that will diminish our dependence on oil and reduce harm to the environment,” he said. But any level of reduction of harm to the environment in the deployment of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles is directly tied to the source of the fuel. While Toyoda said the Mirai could run on fuel that can be made from virtually anything (“even garbage!”), almost all liquid hydrogen was, and is, made using fossil fuels.

It is not just an issue of greenhouse gas emissions and ethics. There is a cost difference based on how hydrogen is made. A “green hydrogen” fill-up for a light-duty vehicle is more expensive than a fill-up with hydrogen made from natural gas. And since cost is key for consumers, it’s likely there will be at least some pushback against setting any goals or firm requirements for hydrogen for light-duty vehicles to use hydrogen explicitly made with renewable electricity (standards for related production incentives in both Canada and the U.S. currently include “low-emission” hydrogen, made using fossil fuels).

The hydrogen fuel cell vehicle cracked the Canadian market in 2018, with the Quebec government saying it would take on 50 hydrogen fuel cell cars from Toyota, with first deliveries starting in the year. The Mirai was retailing for about US$57,000 at the time of the announcement (a 2023 Mirai is under US$40,000, claiming a range of up to about 650 km). For private business, B.C.-based courier company Geazone Eco-Courier was celebrated in 2021, less than two years ago, as having “North America’s first hydrogen-powered courier fleet.”

A leader in the hydrogen vehicle market globally right now is Hyundai, with the Nexo sport utility vehicle. It launched in 2018. It’s currently promoted on the Hyundai Canada site with this statement: “Fueling the Nexo is just as easy as pumping gas.” Claiming a range of up to 570 km, the vehicle is priced at $71,000 (that’s Canadian). Again, the availability of hydrogen to power the vehicle will matter.

In Canada, regardless of make or model, fueling stations are almost nonexistent. Car companies are selling hydrogen vehicles where there are fueling stations, leaving out most provinces. Per Toyota Canada’s website, for example, the Mirai is only available in British Columbia and Quebec.

Fueling up

Finding a place for the regular fill-up is a problem, even if you have a vehicle. There are just under 12,000 retail gas stations in Canada, according to the Canadian Fuels Association. In comparison, you can still count on one hand the number of retail locations offering hydrogen to light or heavy-duty vehicles. There are no hydrogen stations in Atlantic Canada.

The lack of facilities is jaw dropping, not least of all because the lack of infrastructure was identified as a foremost barrier to greater hydrogen use in Canada dating back to at least the 1980s. And it’s a problem not resolved with negotiations with a handful of car makers and a snap of the fingers.

Quickly adding service for hydrogen-as-a-fuel is not just about large oil companies and decisions by big refiners. Canada is a more concentrated market than the U.S., but still only about 20% of gas stations in the country are controlled by the big five major refiner-marketers. The rest are independent owners and companies not involved in the refining process. It means, when arguing for hydrogen refueling to be added within the footprint of existing gas station locations, you need to convince many, independent business owners of the merits. Another option for more hydrogen stations for light-duty service is to site them on new properties. That will mean finding brownfield sites, or zoning new industrial use property, environmental review and community-level permitting, if companies see a business case. And the business case is tough, with so few vehicles on the road. There is no forecast Atlantic Business Magazine has seen on the expected roll-out of fueling stations in Canada; nothing that says hydrogen refueling will become even half as ubiquitous as existing gas stations and certainly nothing specific to this region.

Electric competition

Today, before thinking of how to expand use of hydrogen cars and trucks, the more immediate issue is competition. Frankly, hydrogen fuel cell light-duty vehicles aren’t winning much of the market in comparison to the alternatives of EVs and hybrids.

The report on the latest KPMG Global Automotive Executive Survey, involving 915 executives, stated 70% of respondents expect EVs will reach cost parity with internal combustion engine vehicles by 2030 with subsidies. And 80% of the executives surveyed believe EVs will achieve widespread adoption without government subsidies in the next 10 years.

Politicians in Canada seem content to avoid discussion of the differences in light-duty vehicles. They now often organize all options into the generic category of “zero-emission vehicles” or ZEVs. An advantage for hydrogen proponents in the use of this ZEV label is it allows hydrogen-powered fuel cell vehicles to piggyback on the emerging success story of EVs in the light-duty vehicle market.

To hammer it all home, let’s look at California. It is the largest U.S. state by population and has the most registered vehicles. As data journalist Felix Richter highlighted in 2020, the state’s light-duty vehicle market is large enough to stand up against entire nations. It is larger than countries like Norway, where uptake of ZEVs has been applauded, making a rise in ZEVs in California something that would arguably be an even greater indicator of where vehicle sales are headed. Per government statements, California already boasts more ZEVs than New Hampshire has cars, and the state today has twice as many ZEVs as you’ll find in all of Norway. In 2012, California set a goal of having a cumulative 1.5 million ZEVs sold in the state by 2025. Last month, two years ahead of schedule, Governor Gavin Newsom said that mark was reached. The state now plans to have 100% of new car sales be ZEVs by 2035. In the first quarter, more than one in five vehicles sold in state were ZEVs — the all-in category.

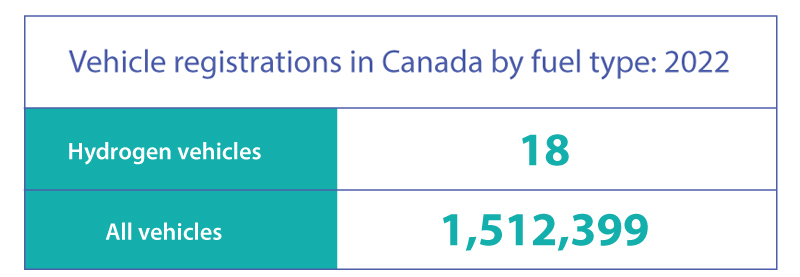

The picture is very different when you delve into the different options. It’s the kind of view of the market you can do easily, with a couple of clicks on a California Energy Commission web page—the kind of user-friendly data page you don’t find in Canada. Right now, even for those familiar with Statistics Canada reporting on vehicle registrations, the agency does not provide a breakdown by vehicle type for Nova Scotia or Newfoundland and Labrador. In response to questions on the lack of available data in some provinces versus others, the agency said it was a data licensing issue involving the provinces. “There are negotiations ongoing with these provinces in order to be able to include their data in the new motor vehicle registrations data, but they are timely. We do not have an estimate for when they will be complete,” a StatsCan rep stated.

But back in California, where it’s easy peasy to get a clear view even by county, and when checked for this story the details showed 588,455 light-duty vehicles were registered in the first quarter of this year, with 124,053 (just over 21%) being ZEV sales. Of those ZEV sales, just 902 were hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. By far, the majority of the vehicles were full electric, followed by plug-in hybrids and not hydrogen fuel cell cars and trucks.

That’s not about a bad quarter or rough year for hydrogen. Of the roughly 1.5 million ZEVs in all of California sales records, only 15,432 have been hydrogen fuel cell vehicles.

And it has to be said the state is unusually far ahead compared to others. It is a leader in North America, with 63 hydrogen refueling stations for light-duty vehicles and another 30 listed as in the planning stages. Nearly half of the available refueling stations are clustered around Los Angeles County, with a smaller service cluster in the neighbouring mid-state counties of Santa Clara and Alameda. At the same time, California’s network of 87,707 EV chargers is highly visible to consumers. EV chargers are clustered too, radiating out from affluent, high-population areas, but the availability in rural and remote areas is still far less restricted than hydrogen.

The more EVs take the market, the harder it becomes to justify the already tough-to-justify distributed hydrogen refueling stations targeting nooks and crannies that might be frequented by light-duty vehicles.

Let’s consider the example of the U.K.’s experience on hydrogen stations, sometimes called “multi-energy” stations, depending on the setup. Last year, specialist publication Hydrogen Insights broke the news Shell quietly closed light-duty vehicle hydrogen stations in the U.K. The publication further reported earlier this month that Motive Fuels was closing two more hydrogen stations near London, based on losses. Motive is a hydrogen-focused subsidiary of ITM Power (where energy and commodities company Vitol made a 50% buy-in just over a year ago). The stations had been primarily for cars. Looking ahead for the U.K., Element 2 Ltd. has promised to provide the first national network of hydrogen refueling stations across the U.K. and Ireland by 2027. It expects stronger demand from heavy road vehicles and municipal fleets. The company got a boost with the announcement at the end of April of a reverse takeover bid by listed company Pineapple Power, while also landing two new refueling station planning approvals.

Large players like GM, Shell and BP are forecasting hydrogen demand in heavy duty transport and other hard-to-abate areas, connecting to the next installment of this series.

Atlantic Business Magazine’s “Hydrogen Horizon” series is a high-level, moment-in-time look at the potential of hydrogen and its associated industry for Atlantic Canada. The level of demand for hydrogen production and the ability for Atlantic Canada to site competitive projects and service the markets, in a rapidly changing global energy sector, deserves serious and continuous evaluation.

Comment policy

Comments are moderated to ensure thoughtful and respectful conversations. First and last names will appear with each submission; anonymous comments and pseudonyms will not be permitted.

By submitting a comment, you accept that Atlantic Business Magazine has the right to reproduce and publish that comment in whole or in part, in any manner it chooses. Publication of a comment does not constitute endorsement of that comment. We reserve the right to close comments at any time.

Cancel